Schede

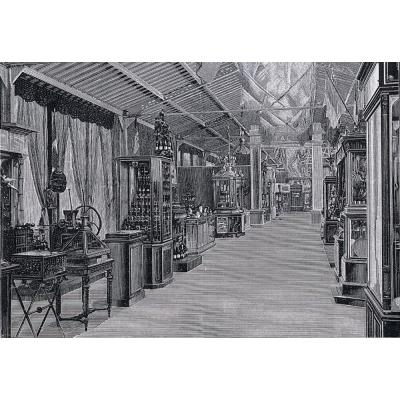

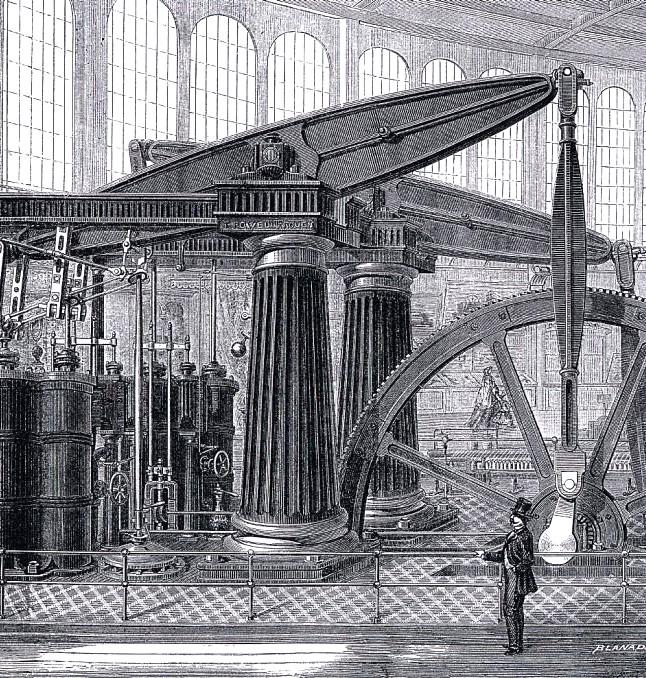

The Universal Exhibitions make their first appearance in London in 1851, thanks to what will be famous in history as Crystal Palace’s Exhibition, taking its name from the greenhouse palace built to host the manifestation: a very big international fair, which hosts every sector of human production, including Fine Arts.

In an ideal view, Exhibitions mark the triumph of the “magnifiche sorti progressive” (“great progressive fortune”) of industrial society: for the countries that organize them, they are a great opportunity, a door toward economy, a force that leads to a spirit of solidarity and cooperation, a place where (encourage/stimulate) contrast and imitation, through an exchange of knowledge, aiming at a general improvement of productive processes. In occasion of Paris 1878, Victor Hugo still sings the praises of the basic ideal principles of the Exhibitions, seen as “… la firma di tutti i popoli posta a un patto di fratellanza” (“… the signature of all the populations at the end of a solidarity pact”). The liberistic convictions are aligned with these principles. Taking into account the impossibility of every country to be self-sufficient, the Exhibitions are seen as the place where to apprehend and evaluate the others’productive reality to encourage commercial treaties and the comparison between quality and price to create a condition of favourable concurrence for the consumers. However, it is only the illusory aspect of a captivating utopia: in the same period when Hugo praises solidarity, the French, repairing behind a fan made up of good intentions, are getting ready to carry out protectionistic measures. These will bring about custom wars, while an idea of the industry as fight and concurrence is beginning to establish.

(In addition/as a consequence), the ideal hopes very soon start to mix up with particular interests. Along with the supportive spirit of former cooperation, for instance, it is demanded to privates to present memories, monographs, production plans meant to help everyone’s improvement and growth, but with bad results. Privates are more interested in getting well-known and in increasing their business contacts, rather than collect and organizing data and information about their own productions to use them to benefit the others. Besides, the Exhibitions are soon becoming part of an initial mechanism of advertisement through the exhibition of the prizes, though (not got) with a particular merit, seeing the great quantity of medals given each time. In the perspective of offering a benefit to the society, the engagement in favouring the “istruzione degli operai” (“workers’instructions”) has been, at least partially, successful. The provincial committees plan to send workers in order to let them exploit this manifestation to increase their knowledge and abilities. In Paris, in 1878, France sends 22.000 workers. The (high days) tickets are sold at reduced price to favour the workers’entrance; there are also special railway fares. In any case, the logic of the Exhibitions, paternalistic and bourgeois, doesn’t let room for the sufferings and claims of the working class; this latter will anyway find its way, making some profit out of those reductions. The Congrés International Ouvrier will be organized in Paris in 1889, together with the Exhibition. The Italian delegation is going to study the Bourse du Travail of Paris and, after its return, due to this inspiration, the Chamber of Work of Milan will be born.

In the Exhibitions, the demonstrative function is very strong, so they are used as a shop window, showing the national power, both from a civil and military point of view. All the countries that, during the XIX century, organize a universal Exhibition, do it to guarantee an advertisement and to testify their international relevance, whether it’s preserved or newly acquired. For example, this is the case of France in 1878, desiring to prove its vigour and (resumption/retrieval) haven’t changed after the defeat of Sedan and the fall of the Empire in 1870; even U. S. A., with the Exhibition of Filadelfia of 1876, want to demonstrate to Europe that the civil war crisis is completely over and that a new powerful economic development has risen from the secession war. Even more significant is the use (done of these events) to organize an indirect military comparison. The nations that take part always accurately organize their own section, dedicating it to the arms. The Krupp, which is mainly famous for steel production, has always at least one cannon exposed, bigger and bigger as the manifestations follow one another. Considering that, for strategic purposes, the diffusion of military exchanges between the European nations wasn’t particularly spread, it’s clear how the frequent presence of explosives in the exhibition stands was firstly featured by political comparison and communication. Political influence rises with evidence during the manifestation of Paris in 1889, organized to celebrate the centenary of the French Revolution. The explicit political message bothers so much conservatory states, such as Russia, Germany, Austria, that the manifestation will count only a few visitors, also Italians won’t be but a few and under privates’initiative. It’s politics, in the end, that gives orders concerning the Exhibitions, by influencing also the expenses: they grow more and more both for the organizing states, who, in most cases, at the end of the manifestation are in deficit, and for the participating states, seen that they often intervene to sustain the transport costs of their exhibitors (transport and arrangement expenses), in order to send commissioners and to buy the most beautiful exhibits. Their excessive width at once provides some problems and the economic aspects are flooded by entertainment and by the “marvellous” ideas meant to astonish the visitors. From the ‘70s, the real interest for economics, which should express in the Exhibitions, gives way to debate about the possibility to open sectorial exhibitions, organized by privates without medals and thought exclusively for the benefit of the workers. Although this, the number of the Universal Exhibitions will keep on being consistent, till our days:

1851 – London; 1855 – Paris; 1862 – London; 1867 – Paris; 1873 – Vienna; 1876 – Philadelphia, U. S. A.; 1878 – Paris; 1880 – Melbourne, Australia; 1885 – Anversa, Belgium; 1889 – Paris; 1893 – Chicago, U. S. A.; 1900 – Paris