Schede

European cemeteries, and in particular those surrounding the Mediterranean, are ideal places to admire the European sculptures of the 19th and 20th centuries. Bologna, as the precocious and exemplary case, anticipated the construction of monumental tombs by forty years. Thus, the Certosa is the optimal place to admire the winding centenary path of artistic trends from Neoclassicism to Realism. The extraordinary context added stylistic and technical particularities in the local funeral memorials. Between 1801 and 1815, during the Jacobin government, almost all of the tombs were executed on painted walls, but with the return of the Papal government, during the Restoration, there was a decisive change in favour of sculpted memorials in plaster and stucco. This evolution was due to the intervention of the Academy of Fine Arts, the authority chosen to approve the projects, which attempted to impose works that were less fragile and delicate, and more appropriate to the memory of the deceased, more mournful. However, the traditional method of using more humble materials remained due to the difficulty of importing marble.

However, the gypsum, stucco, and scagliola, were not a fallback, seeing as how the centuries-old custom allowed them to be used effectively, so much so that our sculptures hardly bothered to emulate the effect of harder materials, and instead created designs that would have been impossible in such materials; such as soft friezes, flowing draperies, figures freely moving without the need of grips or reinforcements, thus supporting attributes that otherwise would have been difficult to create. With unique tenacity, still today, the sculptures in the Certosa are referenced as examples of a deep-rooted relationship with 18th century culture. This continued through the 19th century thanks to the artists connected to the tradition of their own Academy, and who were sensitive to absorb the neoclassical models only superficially. Fortunately, this represents only a part of the vast cultural universe. Meanwhile, it is necessary to better understand which, from the many aspects of Baroque, are still present in the Certosa; those that had a long and substantial influence in the rest of Europe, that Classicism at its highest point, as seen in Guido Reni’s work, continued until the early 19th century through the artistic works of Carlo Cignani, Marcantonio Franceschini, Ubaldo and Gaetano Gandolfi. Donato Creti’s pictorial results predated Neoclassicism for decades due to his admiration for Parmigianino and Nicolò dell’Abate. It was the complex cosmopolitan culture of painters such as Mauro Tesi and of the architect Carlo Bianconi, the latter who was appointed as Perpetual Secretary of the Academy of Brera, that culturally bridged Milan and Bologna.

And even the sculptors who could not work in the Certosa during the inauguration dates, either for age or health reasons, still exhibited, the more or less significant changes in a modern sense. If the late activities of Filippo Scandellari wwere evidence of the superficial bond to the new cultural events, Giacomo Rossi led himself, by constantly removing Baroque elements, to a powerful classicism, and as a point of reference for the next generation of sculptors that will integrate anient greek elements, of the tuscan renaissance and mannerisms. Luigi Acquisti worked in the Certosa. Originally from Forlí and acquiring Bolognese citizenship, he returned to the city after have a long working period in Rome and Milan, with a wealth of experience derived from prestigious public and private commissions. Acquisti was perfectly representative of the transition from the late Baroque to the classicism of Mengs and Batoni, culminating in the more orthodox neoclassicism. The Certosa did not only reflect the cultural orbit of the Academy, but for obvious reasons also that of aristocratic commissions, which were not always aligned with prestigious institute. The tombs of the early 19th century were almost exclusively dedicated to the great aristocratic families, or to the intellectuals in the University, highlighting the great historical tradition but also their political and cultural crisis. The cemetery became a faithful reflection of a city that no longer had a primary cultural role in Europe, but one that continued to be an abundant crossroads for political and geographical motives: a junction between the north and the south of Italy and the second city of the Papal State.

In this context the reference models used to perpetuate the virtues of the dead had, until the middle of the century, the most disparate origins and it is only now that we witness the predominance of consolidated types that can be considered typical funerary characteristics, similar to other Italian cemeteries. Therefore it is not surprising that gothic styled tombs were realised twenty, thirty years in advance of the style’s recovery during the romantic trend, nor of the unsuspected number of Charity allegories, which were understandable only in connection with female memorials, those even with non-aristocratic origins. The particular architecture of the cemetery, such as the absence of the open large fields, rarely allowed the erection of large chapels, and vice versa the predominance of the indoor communal space that led to infinite variations of stems, kiosks, and memorial headstones placed in the entrance walls of the arches, corners, and rooms. Adding to this is the common, but not regular, practice of architects designing the work and the sculptors having a subordinate role. Thus the models were created in the artist’s inspiration, even when they were called both as a designer and creator. For example, in the years 1817-1818, the Conventi and Marchetti monuments were designed by Vincenzo Vannini and the Barbieri Mattioli of Angelo Venturoli were typical, noteworthy for their pyramid design around the sarcophagus: all executed by Giovanni Putti, who at the same time independently proposed the very same plan for the Uttini and Levera tombs. For half a century the local funerary production could thus document all of the artistic currents of the time thoroughly, creating over the decades a rich iconographic catalogue that became an extraordinary incentive to produce printed guides. Five were printed in the course of the century, three of which came equipped with a vast repertoire of engravings that reproduced some of the both more significant and more modest monuments. Additional evidence was revealed in the acclaim of the widely-published, nationally-known magazines such as Il Mondo Illustrato or Cosmorama Pittorico, which demonstrated the Bourgeoisie’s appreciation.

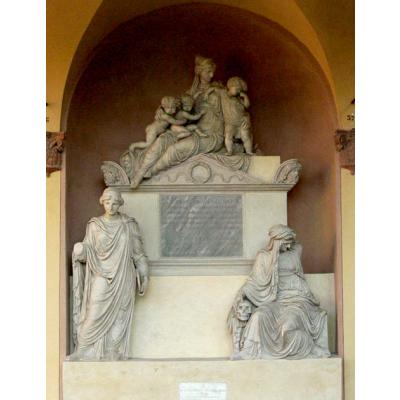

The sculpture, although not that predominant during the beginning of the century compared to the painted memorials, was present in the first years of the century, as seen by the two enormous terracotte located at the entrance of the cemetery, the “Piangoloni”, signed by Giovanni Putti in 1809. The first marble tomb came to light two years after the inauguration of the cemetery, in 1803, and was dedicated to the painter Gaetano Gandolfi. Today’s appearance is different from the original. It was modified to include the bust of his son, Mauro, but during so, the lower part was distorted and it spread a white mantle over his work. The decorations imitating polychrome marble executed by the ornamentalist painter Giuseppe Calzolari were lost in the integration of the sculptural parts executed by Giacomo De Maria and Giovanni Putti following Giovanni Calegari’s project. For a few years it was custom to see multiple artists working in the same yard at the Certosa, so much so that the Baldi- Comi tomb, executed from 1815-16, when a sculpture and two painters worked under the supervision of the designer became the paradigm of the local neoclassicism, very distinct from that which spread from Rome. Whether the presence of painted or lavish polychrome marble memorials was a typical local characteristic was evident from the punctual response in the Ferrarese cemetery, founded in 1813, and from its absence in the Brescia cemetery inaugurated in 1815.

The Bolognese cemetery therefore became a local reference model, both from an architectural and an artistic point of view, for the cemeteries of San Giovanni in Persiceto, Budrio and Imola, among others, that still show, despite the damage caused by neglect and the bombing during the Second World War, marble and painted tombs. When the cemeteries of Staglieno in Genova (1851) and the Monumental of Milano (1867) were inaugurated, the Certosa had passed its “polychrome” phase, and many of the neoclassic tombs were adapted to the new tastes such as coating the walls in white varnish, or with even more black and grey funerals. The marble lasted for a long time as it was a material used with great caution, so much so that the Munarini tomb, executed in 1823, was a rich apparatus of different marbles, applied with thinner and thinner plates, up to the point when the sheet was only a few millimetres thick. This parsimony was not necessarily a symptom of the sculptor’s poor talent of working with marble. Proof of so are the works of De Maria who produced works of great technical expertise and who’s high- reliefs, such as Il Genio, were coronated by the Arts and were delivered to the Academy in 1789 as an essay on his stay in Rome. Giacomo De Maria managed to work in an illustrious manner alongside an architect. The most beautiful allegories for the Vogli and Beccadelli Grimaldi tombs, designed respectively by Giuseppe Nadi and Filippo Antolini came to light. In the Vogli tomb, he achieved a perfect sense of the local sculptures and so the artist created one of his masterpieces, in which the Roman Neoclassism was reinterpreted in the light of local models and iconography. The Caprara tomb, executed a few years later by the same sculptor, was the first monument completed entirely from marble and it deserved numerous acclamations as well as recognition in all the published guides. The Canovian tributes in this sculptor’s works are very evident, and in this relationship are his strengths and his limitations. De Maria failed to organically compose the monument and the sculptures as they appear as individual parts with no communication with the others. Thus, it was not possible to achieve chorality and organicity from the inspirational model: the funeral monument of Cristina of Austria in Vienna. The attempt to adhere to the cultural models that did not fully belong to him was a technique that the sculptor did not repeat. This result had a similar counterpart with Giovanni Putti in the Demaklis tomb, located right next to it. Although their beginnings were different, they added the same horror vacui effect. Giovanni Putti remained a powerful independent artist throughout his career, proud to speak a modern language different from the official one, and he was often in open defiance with the Academy. His creative autonomy in the Ferlini tomb was very clear, as the mention of the 16th century figure frescoed by Niccolà dell’Abate at Palazzo Poggi is evident. One could not imagine anything more distant from the communal conception of Neoclassicism while making it a part of it: and one cannot define it as neo-baroque or worse, late baroque, unless we want to consider also Felice Giani, with whom he shared similarities, if not superimposable, results. The oldest painter, very active in Bologna in the Romagna territory, is an essential reference to understand the many apparent oddities of our sculptor.

The only artist who by reputation could compete with the two above mentioned artists was Luigi Acquisti. Unfortunately, the two large tombs that he created between 1813 to 1818 suffered damaged from neglect and movement between cloisters. Even so, a relaxation can be witnessed in his works, especially compared to the severe Sibille from the Bologna church of S. Maria della Vita and the reliefs of the Arco della Pace in Milan. His work therefore did not carry as much weight to the much younger Bologna sculptors. Alessandro Franceschi is an example of an artist who struggled to find opportunities worthy of his talent. Younger than the other sculptors, he found that he had to compete in often ferocious competitions, of which other internationally famous artists, such as Adamo Tadolini, also had to take part in. His mature works were concentrated in the early twenties and are indicative of his autonomous style, so much so that he gave, as seen in the Badini monument, the most innovative representation on the neoclassic theme of the 'Visit at the tomb'. In the vast funeral yard, however, a large number of sculptors found work opportunities that outside of it would have had few job opportunities, allowing them at least economic survival. Marble and scagliolist sculptors could count on constant work, even if modestly. Among those that made it is possible to consider gregarious sculptures, created more by the lack of opportunities rather than for quality, Innocenzo Giungi stands out. Originally from Romagna, he presented a soft refinement in the Carità for the Soglia Salvigni tomb. Once again the autonomy of our artists comes through in their attention to emotional tension and to the reference of of 16th century, Raphaelesque models. The numerous commissions in these years often repeated similar subjects, and Giungi was known to realize several Dolenti: in this case the artist managed to differentiate the same iconography with sentiments more sorrowful and more dramatic. Our sculptors did not fossilize their repertoires, but they were receptive to the new trends that, after the 1820s, spread from all over Europe. Vincenzo Testoni’s low-relief that he dedicated to Anna Picoski is testimony to such as he re-proposed his design for the scene of the Angelo custode che addita l'ora ad una sposa moribonda that Pietro Tenerani created around 1824 for the Princess Sapieha. The artist later indicated, in a letter addressed to the Academy, that his insipiration for the Carità was from the same theme of the Zacconi tomb (1837), executed by Lorenzo Bartolini. If on the one hand we find that an artist of no importance can justify his choices with models of established artists, on the other we can now see how the models of Canova and Thorvaldsen were surpassed. In any case, as in the lunette for the Bassi tomb, his language appears to be independent, even as he was interpreting the neo-atticism taste of Alessandro Franceschi.

In Bologna’s cemetery there was a progressive decline in commissions between the years of 1830-1850, as the aristocratic families had already finished their monumental tombs and the smaller middle class families of farmers and merchants did not have great economic capacity, so their requests were mainly small stems and cippi in which to engrave on their memorials, and in so, the sculptor was most responsible for the execution of the portraits. This was due to the economic crushing of the Papal state to our city during the years of the carbonare conspiracies, insurrectional attempts, and Risorgimento battles. Alongside the secular values firmly represented in the Certosa in its innumerous allegories, it was during these years themes related to the Christian religion begin to resurface. Neoclassicism was already turning into Purism and the Canestri tomb, created by Massimiliano Putti in 1841, announced its arrival. Unsurprisingly, it was the son of Giovanni who executed it and who, following in his footsteps, could count on a solid cultural and technical base. Moreover, seen in his father’s later works, such as the Betti tomb of 1828, there was a sense of change and Massimiliano, well-integrated in the local academic world, had the means to continue in this long project. In the marble Canestri monument, he offered a sweet mediation between neoclassicism and Renaissance in the lower part, and in the upper lunette he represented the Buon Pastore, a reference to early Christian iconography. From this moment he became the absolute master of the most prestigious commissions and his works kept up with the significant number of marble requests required by the famous, foreign artists such as Duprè, Vela and Strazza. The forty-year artistic career of Putti, always of quality, highlighted the cultural changes of the century up to the Realism of the 1880s, the expression of the nascent bourgeoisie. Without his impressive marble catalogue and his academic activities, Putti’s extraordinary developments for the following generations, Carlo Monari and Enrico Barberi, could not have been understood in the first place.

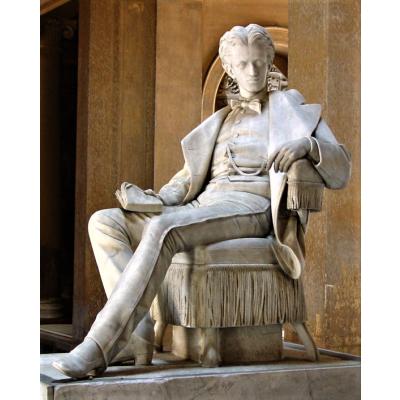

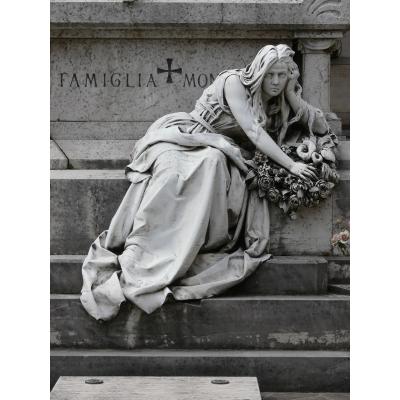

Cincinnato Baruzzi worked in this context, returning to Bologna after a decade spent completing the commissions that Canova had left unfinished in his Roman study. His devotion to classicism, which approached Naturalism almost exclusively in his female nudes, did not allow him to create models for the cemetery. The Pizzardi tomb, with its rightly described allegories of Greek-inspired and sumptuous in the magazine Il Caffè di Petronio in November 1841 was an antithesis to the Canestri tomb and remained a point of arrival, not a starting point for the local sculpture. In Massimiliano Putti’s final work, completed just before his death, it was possible to observe how he adapted to the new style of realism with the relief depicting Ulisse Bandera sitting in an armchair. At the end of the 1880s this was a familiar iconography used in the funeral environment, and the first local example was due to the young Carlo Monari, who with the design by Enea Cocchi created a splendid version in 1867, contemporary with similar subjects executed by Vela and Duprè. To this young artist we owe the most innovative catalogue in our cemetery. Predominately active in the 1860s and 1880s, despite coming from a classical culture- he was responsible for the marble transposition of the Eva marble that Baruzzi had modelled for his own tomb-- expressing itself immediately with coherent realism. He gave us many sorrowful women gathered at the boundaries of the tombs, with all the apparatus of crinolines, silks, and laces of their clothes. Apparently his triumph came from within the bourgeois iconography in the cemetery of Staglieno in Genova, where he veritably profused young women, inconsolable widows, tearful children, and orphans grieving for their lost loved ones or benefactors. Monari was certainly a part of this cultural trend, but he managed to keep his stylistic identity, so much so that in his figures it is always possible to see the volume of space that they occupy, their weight, and an ideal contour line that encloses them, avoiding the usual expansion in space with showers and all sorts of accessories.

Other artists active in the same years as Giuseppe Pacchioni had difficulty to escape the correct, but cold and forced academia, found their largest freedom only in their portraits. Francesco Bonola managed to receive commissions of a certain importance, but his realism was not fully understood and therefore it was no coincidence that his best marble, created for the family tomb, was adapted from an iconography decades old, like the Fiducia in Dio by Lorenzo Bartolini. Unfortunately, three talented Bolognese sculptors were not able to express themselves fully and the scarcity of their known works does not allow for an objective understanding of their artistic careers today, even if the local school continued to give light to different personal variations in this moment of transition. Alfonso Bertelli, Federico Monti and Alfredo Neri had to clash in a new ruthless competition, crushed between the great commissions given to Putti and Monari or to Cento’s Stefano Galletti and Livorno’s Salvino Salvini, the latter two were long-active in the cemetery and had gained national prestige. Among the works of these artists we remember the low reliefs for the Pallotti tomb by Bartelli, and the marble depicting l’Anima accompagnata dall’Angelo from the Romangoli chapel made by Alfredo Neri. An entire generation separated them but through these two sculptors we can understand how local classicism could find new life in the Liberty trend, skipping Monari’s realism, and in turn, be insensitive to the new styles and be commited to following a completely autonomous path. Federico Monti’s relief Genio della riconoscenza, sculpted in 1863 for the Bertocchi tomb, was a significant commitment for a sculptor in his early twenties. This marble, designed in total adherence to the neoclassical models, shows, in the executive phase, an attention to the naturalistic and romantic taste, so as to reach a frozen sensuality in Genio.

The Bolognese cemetery remains to this day a place to confront differences t artistic trends. The Joachim Murat by Vincenzo Vela and the Bolognini Amorini monument by Stefano Galletti, both dated to 1864, clearly show how one was an expression of the new realist trends and symptomatic of reforming ideals, while the other relied on classicism to express conservative ideals. In this context Bolognese sculptors, though driven by an attachment with local traditional subjects, had the opportunity to express themselves with themes more romantic, more sensual, or realistic. Participation in national and international exhibitions, the massive dissemination of increasingly illustrated art magazines, required even the more modest artists to adjust. In the following years, now close to the twentieth century, the proliferation of commissions allowed for a vast and varied production, ranging from the typical portraits to large marble groups. Bronze started to make its appearance and the artists were called to satisfy an ever-growing clientele. The materials produced inside the Certosa assumed significant dimensions, so much so as to push foreign artists such as Cesena’s Tullo Golfarelli or Ferrara’s Mario Sarto to make it their permanent place of work. The final movement to Bologna in the 1860s by the marble firm Davide Venturi & Son was explained on the one hand by the need to support sculptors in large funeral homes and public commissions, on the other to satisfy an increasing demand for replicas and ordinary sculptures for a medium-low clientele. It is not surprising that the marble created for our cemetery spread throughout the Romagna area and beyond with replicants and variations of different types and qualities.

It is not possible to compile a list of all of the sculptors active during the nineteenth century- thus dozens of painters and architects are excluded- as it would add up to more than sixty signatures, many of which whose personal details still need to be found. However, the relatively high number indicates how the Certosa was an extraordinary site for sculptures that for most of the 19th century no other nation in Europe could be compared. In the 1880s, the city of the dead also witnessed a generational overlap where, alongside the established masters, also worked young artists, all engaged simultaneously in the most commissions. Carlo Parmeggiani and Diego Sarti, born respectively in 1850 and in 1859, continued their activity in the first decade of the twentieth century, guiding the local tradition towards the Liberty style. Sarti was responsible for important works of public decorum, broadening the artistic themes beyond that of funerary. In the Certosa his feminine figures softened their sensuality of the Sirene placed in the garden and at the staircase of the Montagnola garden, so much so that the Dolente for the tomb of Osti can perfectly summarise the path that, from the romantic disturbances of the Desolazione by Vela and Felsina by Lombardi, both in the Certosa, led to the new softness and sinuosity of the style of Art Nuoveau. His final work indicated a further evolution. The Bonora chapel, dated 1909, was purified from any decorative element and everything is displayed on a green monochrome. The Christ lying on the shroud was compressed by an atmosphere of death, ingeniously evoking a just air of dominance. The Allegory of Architecture by Parmeggiani for the tomb of the architect Tito Azzolini was, on the contrary, decisively less funeral, almost a stylish art illustration.

To this adherence to international taste is also added the local varient of the English Arts and Crafts by William Morris- the Aemilia Ars - which was interpreted in the Certosa by Tullo Golfarelli and Enrico Barberi who, though distant in their political and cultural ideals, were both called to contribute to the authentic, “total works of art”, in which sculpture, architecture, and craftsmanship merged together with the highest level of results re-proposing in modern way the collaboration between the artists from the previous century.

Roberto Martorelli

Translation from italian language by Holly Bean.