Schede

Observe how marble research was presented in the last decades of the 19th century in Alfonso Panzetta’s essay Sculture: dal primo Novecento al Figureazionism Contemporaneo in which the three artistic renovation directions that took place at the beginning of the twentieth century are described. The first movement was represented by Realism in its unprejudiced analysis of the contemporary society deprived of any romantic idealisation (V. Gemito, A. d’Orsi, V. Vela).

The second unique movement began in Lombardia called Scapigliatura, which opposed the power of the Academy for a more picturesque sculpture (M. Rosso). The third direction, in which the new generation of sculptors arose as the protagonists of the artistic renovation in the Certosa, continued the 19th century academic tradition of eclectic realism in which monumental and celebratory rhetoric converged, well-evidenced in the public commissions and in the monuments for fallen soldiers of the post-war period. These artists initially adjusted to the Liberty-symbolist climate and had its greatest Italian representative, Leonardo Bistolfi, and around the 1920s the spread of the popular Dèco taste. With these elements, in the last decade of the century, they added various local ferments, which had a large influence on the cultural change of the city. In 1894 the Francesco Francia Association of Arts, which offered an interesting occasion for various generations of artists to be compared through periodic exhibitions, was born. Attention to what happened ‘beyond the Alps’ influenced the formation of the Aemilia Ars in 1898, a joint-stock company founded on the aim to promote and redevelop the decorative arts and everyday objects based on the example of the English Arts and Crafts. Among the founders of experience, which ended its brief production in 1903, were Count Francesco Cavazza and Alfonso Rubbiani, a charismatic figure of architecture, restoration and history, around whom revolves a guild of artists intent on recovering the medieval face of the city through various works of restoration. Between memory and renovation, the Aemilia Ars inserted new symbolist and liberty poetics into the renewed popularity of Gothic and Renaissance art that was supported by a reference to the medieval organisation for artisan work.

Linked with the styles of the 19th century, albeit with original results, was Alessandro Massarenti (Minerbio, 1846- Ravenna, 1923), who held the chair of sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts of Ravenna from 1872 to 1922. He was a student in Bologna under Massimiliano Putti and Salvino Salvini, he finished his studies in Florence with Giovanni Duprè. Attentive to the lessons of his masters, as can be seen in La fanciullezza di Raffaeollo of 1876, in his mature years he moved away from the purist language and from the romantic naturalism of Duprè for a more anecdotal realism and away from strong sentimental connotations of sculptures such as Babbo ho fame! and Vi ricordate? exhibited in 1883 in Rome. Presenting in numerous national expositions, Massarenti was very active in the cemetery area of Bologna and of Ravenna, where he left monuments of great marble quality, mindful of a bourgeois Realism. Among the most impressive works in the Certosa is the Zanichelli tomb of 1886, which displays the severe marble bust of the publisher Nicola supported by an elegant motif with strongly symbolic vegetable and animal symbolism in the pilasters. In 1889 the sculptor, while modelling the burial of Angelo Minghetti, the founder of the same-named ceramic company, achieved unprecedented results. The monument was entirely made from maiolica, a unicum in Bologna’s cemetery, and contrasted the portrait with the strong vertebrate accents of the deceased against the Rabbian lunette and the thick neo-Renaissance decoration. A contemporary to Massarenti, with whom he shared a similar academic background, was the Bolgonese sculptor Enrico Barberi, an emblematic figure of an academic eclecticism exemplified in one of his most spectacular works such as the Bisteghi marble monument in 1891. A meditative artist, he obsessively cared for each detail from crude realism of the deceased to the meticulous rendering of materials, faces, the neo-Renaissance carving of a bed. The contrast between these elements and the majestic angel with its liberty accents highlight the importance of Barberi in mediating the artistic climate of the 19th century with the new symbolist and liberty taste that was spreading across Europe. The artist, who long-held a position as Chair of Sculpture, played a key role in the academic field in which he had the delicate task of leading young students, such as Silverio Montaguti and Giuseppe Romagnoli, into the new century. The Cavazza monument of 1893, with Barberi’s Cristo with its strong veristic details and the late Gothic altar made from delicate marble with thick neo-Renaissance decoration and pomegranates, is one of the first examples in the Certosa of the new Revival taste that was spreading in the city, thanks to the work of Rubbiani and his guild of artists.

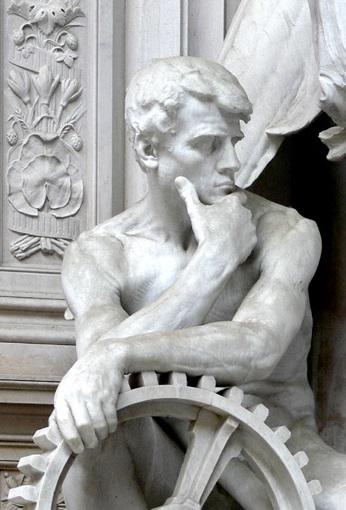

Cesena’s Tullo Golfarelli was also well integrated in this cultural climate. His long artistic career demonstrated the continuous and harmonious updating of his works with previous styles. From Bartolini’s La Flora reminiscent of Salvini’s classical instruction transitioning to Neapolitan realism with works such as Settembre and Musica rustica, presented in 1888 at the Emiliana Exposition. In 1896 Golfarelli became well-known in the Certosa for his monument to Gaetano Simoli, where the young municipal blacksmith became the emblem of the exultation of work, as described in the article “Il Resto del Carlino”; in the event of his presenting the new tombs at the city’s cemetery, noted that the modernity of his works produced an effective impression: “minds think ‘omnia vincit Labor.’” In fact, his friend Pascoli described the artist as a “sculptor worthy of Giosuè Carducci”, “sculptor of the workers,” revealing the common approval for the progressive cultural circle that gravitated around the poet. Originally placed in front of the Simoli sepulchre is the tomb of the Stoppani family constructed in 1903 and later transferred to Cloister IX. On a marble plinth stands the realistic bronze figure of the merchant Giambattista leaning on his walking stick while looking serenely ahead. The work was almost a pendant to the blacksmith Simoli who became, in this case, the bourgeois manifestation of enrichment through honesty and integrity in one’s work. The chapels of Gancia (1896) and of Cillario (1905) were totally different in style, in which Golfarelli demonstrated his attention to the changing artistic climate that revolved around the Rubbianesque Guild and the Aemilia Ars. Both were designed by Attilio Muggia, with the intervention of Achille Casanova in the mosaics and by Golfarelli in the marble groups, they represent the happy marriage between the Neo-Renaissance references, symbolic motifs, rich polychrome decoration and liberty concessions. For the Gancia chapel, the sculptor created the graceful Angelo della Fede and an elegant frieze with the motifs of a vine and a procession of sorrowful putti representing the allegory of the wine trade that awaited the family. The angelic figure was repeated in the adjacent Cillario chapel, where the artist placed two celestial creatures kneeling in adoration at the cross. Golfarelli’s angels, with their flowing hair, delicate feminine faces, swirling draperies, are certainly humanised but they are far from the sensuality and mystery of symbolist and and decadent images.

Close to this sense are the works of Diego Sarti, a precursor of the new liberty-symbolist style as seen in his fountain in Margherita Garden created for the Emiliana Exposition in 1888. His sea nymphs with their garlanded hair and their wild, mischevious aquatic games show the sensual style of neglect treated with the loose lines that were typical in the stylistic innovations spreading across Europe at the time. These elements combined with a decadent sense of decay and death can be seen in the Dolente of the Montanari monument created in 1891 in the Certosa. Of a completely different artistic style is the adjoining the female figure, “in a very simple and perhaps too modern toilet” (as described in “Il Resto del Carlino”) that Pietro Veronesi modelled kneeling at the sarcophagus of the Berselli family in 1902. The comparison to his previous works underlines Sarti’s early novelty and his adaptation to the more conventional realism of Veronesi. As prolific cemetery sculptor he revealed a rare skill in modelling marble but unfortunately it was not enhanced with his artistic choices when he stayed consistent with the academic canon, as demonstrated by the Assiduità of the Riguzzi sarcophagus (1897) or the woman gently reclining on large chair on the Giacomelli tomb (1909). Some of his more original designs were found instead on the Gangia monument (1901) or on the unusual ‘Christ’ iconography of the late liberty style as seen on the Bonfiglioi tomb (1924). The most interesting of Veronesi’s works was the Luigi Gallina tomb created in 1904. The well-known horse merchant was depicted on a similar bust placed on the top of the sarcophagus and in the center of a riding scene, a reflection of the immediate reality outside of the burial area. The works executed in the Certosa by Arturo Orsoni are more adherent to the liberty sinuosity. He trained at the Academy with Salvini, and he combined the idealisation of form and image with the bistolfiano lyricism in the Poggi tomb (1896); the mystical faith was executed more adherently to the academic canon and can be seen in the Pietà of the Benni cell (1909). These elements reoccur also in the Angelo created in 1916 on the sarcophagus of the Nannetti family. Orsoni’s harmonious modelling was revealed in the the soft folds of the garment that outlined the body of his celestial figure like an impalpable veil. The Bormida relief of 1922 is fully adherent to the late Art Nouveau style.

The work was thus described in the “Il Resto del Carlino”: “a young maiden laid crowns on the tombstones of her mother and her young musician brother. In the background a vision: the beautiful mother smiles at the sound of a paradisiacal instrument touched by her son, already transformed into an angel.” The softness of the drapery, the wavy and undressed line, the elegiac character of the scene, the veiled woman of classical memory are all elements that do not betray Orsoni’s stylistic convictions. With the linearity of the low relief made in 1902 for the tomb of Dioniso Antonio Clazoni, the sculptor and decorator from Bologna, Gaetano Samoggia, demonstrated his alignment to the floral style of the Aemilia Ars. The rich decoration with a dense branches of pomegranates and flowers rising behind a young Mercurio was expertly stylised by the sculpture, giving the work of a strong pictorial effect. An active collaborator with the Rubbianesque Guild, he assisted in many works of restoration and in 1904 the decoration of the Boschi chapel in the Bolognese church of San Francesco. The previous year, with a floral motif in relief, he took part in the preparations for the reserved room of Aemilia Ars for the Emilian artists at the Venice Biennale.

The liberty style of the artists hardened into the sharp lines of the dèco style in the relief of the monument Francia (1917), where the symmetry of the two angels and the almost geometrically sharp contours are the peculiar characteristics of this style. Of such great aesthetic quality are the works of two Bolognese artists, who were among the most significant interpreters of the cultural climate in the first decades of the 20th century: Silverio Montaguti and Pasquale Rizzoli. This latter, who will be analysed extensively in the chapter dedicated to him, left in the Certosa monuments of remarkable scenographic impact in which joined the liberty and symbolist modules with the strong volumetric and marble language of Adolfo De Carolis. From the beginning of the century we witnessed an artistic spread of Michaelangiolism inserted in the celebratory climate of pre-war Italy. Bistolfi also paid more attention to the anatomical study aligned with the Neo-Renassiance memory of De Carolis. Both artists were in Bologna in 1908 when Bistolfi was commissioned for the Carducci monument, while De Carolis won the competition for fresco decoration of the Palazzo Podestà salon. Their direct contract with the local cultural environment certainly affect our artists by influencing even the late cemetery production of Montaguti, as demonstrated in Maternità on the Riguzzi tomb (1922). The commissions in the Certosa offered an interesting panorama of the artist’s constant stylistic updating. Hints of the liberty-symbolist of the angel of the relief De Napoli (1905, fig. 3) became stronger in 1911 with the monument for Benedetto Zamorani, a rich landowner mistakenly confused in the previous literature with the founder of “Il Resto del Carlino” Amilcare Zamorani. This work splendidly inserted in the typical Bologna floral style, gave way in 1913 to the turning point of Angelo Magagnoli and then declined in the 1920s with the rise of the dèco language as seen in the statue of Dolore of the Rimini tomb. Another splendid example of Montaguti marble quality was seen in the symbolic group created in 1926 for the Zironi tomb, where the most incisive figure was not Mercurio whose vertical extension dominates the entire composition but the Tempo, curled in a refined pose ready for the treacherous shot.

The artistic production of Arturo Colombarini (Bologna, 1871-ivi, 1940) was placed between the Neo-Renaissance and Liberty languages. After his work on the marble Bononia Docet of 1895 and his impressive decorations of the Montagnola staircase, which also included the works of Sarti, Veronesi, Golfarelli, Orsoni and Ettore Sabbioni, he collaborated with the Rubbianesque Guild to restore the church of San Francesco. In the Certosa he signed a few emblematic works that adhered to the bistolfiani style, evident in bronze for the Fabbri family of 1906, otherwise in line reminiscent with prewar architecture enriched by elegant friezes in the floral style by the Foschini stele realised in 1912. One of the more refined sculptors active in the Certosa during the first decade of the 20th century was Bologna’s Giuseppe Romagnoli. Sophisticated interpreter of the Art Nouveau, in 1901 he created the Angelo of the Saltarelli cell, mindful in his formative years of classical and Hellenistic statues, but perfectly in line with the symbolist details of secular and sensual angels. The floral frieze placed on the side of the robe returned with lilies in the high relief of the Albertoni cell completed in 1909. The evanescence of drapery enhanced by the whiteness of the marble is animated by a moving line that made the work among the most elegant interpretations of the sensual and mystical sensibility typical of Bistolfiano liberty. As it was described in “Il Resto delCarlino”: “an immaterial lightness is in the immaculate body that death had rendered pale: two consolers barely touch her transparent hands, welcoming the young women into the miserable reign of death. On the other side, two companions hasten with the dresses already ventilated”. The creature’s ethereal dance is calmer on the monument of Enrico Guizzardi (1911), where the artist shapes two graceful figures to the sides of a herm and the portrait of the deceased is placed on the top of the tomb. The veiled woman wrapped in soft drapery sadly lets roses fall on the tomb while the tomb while the male figure frees himself from the matter in a sort of unfinished Michaeangelo, looks ahead with noble pride. A student at the Barberi Academy, Romagnoli immediately showed his sought-after talents as a modeller with skill in various artistic languages. In fact, in 1897, he was awarded the prize at the Venice Biennale with the Ex Natura Ars that he sculpted in line with the realistic style of Gemito, while the following year he won with the Baruzzi prize with Crepuscolo, now conserved at the GAM, demonstrating his knowledge for the symbolist lessons. In 1902 he participated with Aemilia Ars, of which he became a regular collaborator at the Universal Exposition of Torino, which placed him in direct contact with the international liberty climate. His affinity with this society and to Rubbiani led to his involvement in the preparations for the Emilian hall at the Venice Biennale in 1903 and in the restoration work in San Francesco. From 1909 he settled in Rome where he was appointed director of the Royal Medal School. For his chisel work of medals and coins for the Kingdom and the Italian Republic supported his important commissions, such as Gloria for Vittoriano or the group Fedeltà allo Statuto for the Vittorio Emanuele II bridge.

Alfonso Borghesani was also present in Bologna’s necropolis, a sculptor with elegant narrative abilities enhanced through a pictorial use of bronze, evident in the works of the reliefs of Steno Torchi of 1923 and Alfredo Testoni of 193. During such time the liberty language was flanked and updated with suggestions of dèco and the twentieth century, although it was never surpassed. The monument for the Bonora tomb of 1921 in which portrayed the Tre Marie dolenti sul corpo di Cristo morto were depicted, in fact, with dèco influences in the repetitiveness of the female figures whose drapery was modelled with straight and thin lines. The use of coloured material seen in many of his works left room for the white marble of the relief for the tomb of Giuseppe Ruggi, the famed Bolognese surgeon (1925). Borghesani gave the hard material the sense of the divine light as seen in the Redentore tra due angeli. Each detail from the flowers at the feet of Christ to the wavy and soft drapery was fully included in the now late Art Nouveau style to which the artist always remained faithful as documented by his works of the late 1920s for the Dalmonte and Milani burials. However, the symmetrical and frontal layer with the linear folds of the robe in Salvatore demonstrated an attention to the new artistic ferments evidenced in the last signed monument built in the Certosa in 1942 for the Borsari family, where the two figures embrace the door which crosses over to the afterlife were in perfect alignment with the 20th century classicist language. One of the least valued and studied artists, Borghesani gave several works to the city, including numerous memoirs in the university building of Palazzo Poggi, reliefs for the Alberani house, bronze commemorative plaques for postal officers who died during the Great War in the atrium of the Post office building. The prolific cemetery production of Mario Sarto, a sculptor who shared with Veronesi an entrepreneurial interpretation of artistic activity, became a director of the marble company Davide Venturi of Bologna before working on his own. His discrete exhibition activity, with his presence in 1917 at the Società Francesco Francia exhibition and in 1922 in Turin at the Promoter of Fine Arts, accompanied the cemetery commissions with a constant adherence to the liberty style left room in the 1940s for the rhetorical exultation of the Fascist-era hero of the sarcophagus for the pilot Ezio Parenti. Skilled in working with marble, Sarto created the Fantini and Sabbioni tombs in 1912, where alongside the usual scenographic iconography of the angel who accompanies the soul to heaven, he first combined the executive mastery of the second in which in a single block of marble he sculpted a young girl wrapped in evanescent veils surrounded by roses. Sarto also used various materials for decorative and chromatic purposes, such as the monument of 1924 of Maria Beatrice Comi, in which in a refined golden mosaic derived or simple reminiscent of the local experience of Aemilia Arts, with bouquets of white lilies stand out as symbols of purity and innocence. With an essential thanks to Liberty, the artist did not renounce the lightness typical of this style, exemplified in the ascending movement of the entire composition, although some compositional details were flattened or stiffened to imply hints of déco in the symmetrical line of the two celestial figures, whose wings are sharp outlines that reveal a synthetic treatment of the form. In the same years, according to “Il Resto del Carlino,” Sarto created the allegorical group that decorated the Marangoni tomb, where a central mosaic on a blue background interrupts the dark bronze of the sculptures. The artist aligned with the new language of the 20th century through a compact and models demonstrating an artistic versatility wrapped in the needs of the client.

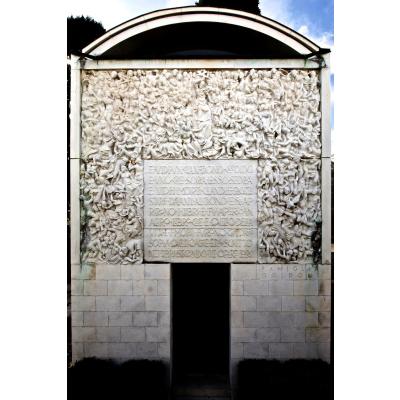

The long stages of liberty and symbolist that after offering a final radical, iconographical renovation in the cemetery, were stylistically exhausted with the intervention of the Italian artist Armando Minguzzi. Studied at the Barberi Academy, he combined the formal marble of his sculptures with the floral taste learned at Rizzoli’s studio and revealed in the female figures, an allegory of Tempo on the Vegetti tomb. With the Raggi Ruggeri monument of 1928 he attained a level of compactness that was formal and volumetric typical of the twentieth century sculpture. Dedicated to two motorcycle champions, the large bronze high-relief was completely included in the new artistic climate also for the theme which praised the daring sportsmanship that was so dear to the Fascist era, and whose obvious influence came from the Roman salute of motorcyclist parade that paid homage to the fallen heroes. In the 1920s and 30s, despite the changed social and political climate, which had the most rhetorical models of brave sacrifice for the homeland in the monuments to the fallen of the Great War, we witnessed a change from florals models to the déco style. With the new generation of artists working at the turn of the Second World War, the 20th century suggestive artists such as Sarto and Minguzzi were consolidated through a treatment of the memorials, reminiscent of classical statuary. The artist who was key in this stylistic passage as he held the chair of sculpture at the Academy from 1927 to 1957 was Faenza’s Ercole Drei. Trained in Florence with Augusto Rivalta, even in his first sculptural essays he proved to be a sculptor who surpassed the realist and naturalist education through the sinuous passion of works such as Cassandra, the winner of the Baruzzi prize of 1910. After joining the bistolfiana brand of Liberty which combined déco linearism and neo-fifteenth-century intentions, evident in his sculpture La morte dell’eroe, which won him the Pensionato Artistico Nazionale in 1913, the arrival of the volumetric importance of 20th century classicism with published works such as Quadriga of 1928 for the Palazzo di Giustizia of Messina o l’Ercole for the Stadium of Marble in Rome. Borrowing from this language were La Forza and La Gloria, allegorical figures created from travertine in 1932 for the Memorial to the Fallen Fascists of the Certosa. The compact marble of the two statues became emblematic of the Mussolini era in the robust angels making Roman salutes, an allegory of Glory. In the Lamberti tomb of 1954 and in the statue La Nottedella in the Barbieri tomb, their gestures sheltered their sadly reclined faces, Drei created the most elegiac works in which the classicism of the 20th century was mediated through the sinuous liberty monuments and déco memories.

After the Second World War, a serious of monuments, in which there was a revival of religious allegories and themes with their high social value implications, were built in the Certosa. The artists that signed these works combined the lessons of Drei with the archaism of Arturo Martini. Bologna’s Farpi Vignoli, a sculptor known internationally thanks to a serious of dynamic works inspired by sport, one of the beloved subjects of the Regime, modelled the original Frassetto tomb in 1950, where he lays in conversation, like on a triclinium, is the famous anthropologist Fabio and his son who died in the war. The celebration of individual professions can also be seen on the Gnudi tomb in 1951 with its social implications. Ennio Gnudi, a trade unionist and anti-fascist, sits on a classically designed sarcophagus and is supported by the workers he represented in the workers’ struggle. In these works of travertine the artist abandons the softness and fluidity of his athletes, such as Il Guidatore di sulky of 1936 or Il saltatore of 1939, for a more compact and dense marble. One of the most celebrated works during those years would be the refined monument of Edoardo Weber (1954-1957) by Venanzio Baccilieri. An artist with an undeniable talent in marble, he created with an elegant clarity, on his tomb an eclectic sarcophagus, frozen episodes of various stages of Weber’s working life in the carburettor factory of the same name. The formal purity of these low reliefs placed the artist in direct contact with the paintings of the period, confirming its isolation from classicist rhetoric. Similar themes can be found on the reliefs of the Minganti tomb (1947) and Capi (1955) made by Bologna’s Romano Franchi. He represent Giuseppe Minganti, founder of the namesake mechanical office and Giuseppe Capi, typographer, supported their works, thus exemplifying the same dignity of the two social classes. The restoration work following the damage caused by the bombing of numerous city buildings during the Second World War extolled Franchi’s predilection for pre-Renaissance sculpture of which the religious cemetery monuments are indebted.

Fully featured in the conventional classicism of the second post-war period were the works of Renaud Martelli, one of the most active sculptors in Bologna’s cemetery. In his works he recalled the 19th century late romantic motifs, such as the kneeling young woman with strong sentimental connotations of the Ropa tomb, joined with symbolist details in the Angelo placed under the allegorical relief of the Agricoltura of the Largaiolli tomb (1947, fig. 22). This analysis closes with the best known and most appreciated international sculptor in Bologna, the works of Luciano Minguzzi. Son of Armando, his works in the cemetery ranged from the Cristo risorto of the Fanciullacci cell to the symbolic and desolate tree of the Atti tomb. Worthy of note is the door of the Baravelli sepulchre of 1967 in which the artist, through very personal and synthetic expressionism formed San Luca and San Paolo with two symbolic episodes of their life in four panels.

Federica Fabbro

Translation from italian language by Holly Bean.