Schede

There is little and uncertain information about the first jewish settlement in Bologna in the III and IV century A.D. because of the lack of documents which doesn’t allow a reliable reconstruction. The first historic evidence is from 1353: it refers to Gaio Finzi “Judeus de Roma”, who lived in the city and was a ragman. Just from the second half of the XIV century stands the large and stable presence of a group of Jewish settlers in Bologna, from Fabriano, Orvieto, Rimini, partly pawnbrokers, regulated by a code of conduct of the city authorities, that is a contract which established the agreement between the parties. The attestations about the silk and clothes traders and the ragmen, the printing business are numerous and there is also information about more humble jobs (tailors, shoemakers and hawkers). When the city came under the domination of Bentivoglio and then under the direct pontifical domination in 1506, the relation with the Jewish minority didn’t crack and indeed new settlements have been attested and a growth of the community in the city and in the country. The economic significance facilitates the renewal of the regulations and the maintenance of the relationship which doesn’t go into crisis, even when a pawn shop was founded in Bologna in 1473.

The Papal bull “Com nimis absurdum” of 1555, promulgated by pope Paolo IV, represents a significant change in the political attitude of the Church towards the Jewish minority and the evident intention was to cut off every relation between Christians and Jews, who from then on should live in an assigned district of the town, the ghetto, which was bounded by walls and gates. The relationship is permanently cracked when in 1569 the bull “Hebraeorum gens” forced the Jews of the pontifical domains to leave the city, except Rome and Ancona; from Bologna about 800 go away. When, in 1586, they are readmitted in every town of the Papal State, some Jews went back to work in Bologna, but after the bull “Caeca et obdurata'' of 1593 by pope Clemente VII, the few Jews readmitted, were forced to leave permanently. Between the end of the 14th century up to 1593, the year of the expulsion of the Jewish people from Bologna, the city was one of the most vibrant centers of the Jewish culture in our mainland. Evidence about that was, by the way, the reference of the representatives of the Jewish community of central-northern Italy, which took place in Bologna in 1416; the institution in 1464 of a professorship of Hebrew (ad litteras hebraicas) at Studio bolognese; the establishment of a Jewish typography in the last decades of the 15th century and another one in the first half of the following century; the practice of many Jewish doctors; the birth of a well known school of Talmudic studies (bet midrash), founded and headed by Ovadya Sforno in the first decades of the 16th century. Moreover, by the cross of the migration flows determined by the expulsion from the neighboring countries, in Bologna the Jewish tradition was embellished with the contributions of the Sephardic and Ashkenazi culture; the result was the development of a thriving activity of copying and decoration of the Jewish manuscripts of a religious, literary and scientific nature. In the 17th and 18th centuries there aren’t testimonies of a stable Jewish community in Bologna, because the pontifical edicts imposed bans and limitations about settling down and living in the city. After the proclamation of the CIspadane Republic in 1796, in the septembre of the same year the napoleonic army entered Bologna, extending the Constitution, on the french model, which guaranteed the legal equality to all citizens and established that non could be persecuted for religious reasons: the Jewish could again live in Bologna and become full citizens, obtaining the freedom of religion. In 1815, Bologna returned again under the domination of the pontifical govern, which reinstated and reconfirmed the previous bans and abolished all the civil and political rights obtained thanks to Napoleon Bonaparte.

The condition of inferiority and the discrimination of the Jews in the Papal States through this period was widely documented; in order to react to the discriminations and the injustices, many Jewish people took part in the Risorgimento uprisings of 1830-1831, then in the insurrection on the 8th August 1848 against the Austrians and the representatives of the pontifical government, few months after the concession of Carlo Alberto of Savoy to the Jewish of Piedmont, Ligury and Sardinia of an emancipation paper and of the recognition of their civi, political and religious rights (the 29th March 1848). From 1849, instead, pope Pio IX established new restrictions for the Jewish in Bologna, relieved only by the solidarity of some Bolognese captured by the matter of freedom and emancipation of the Jewish. This last period of awe was marked by the story of the Jewish child Edgardo Mortara, taken away from his family the 23rd of June 1858 by order of Holy Office, because baptized without the knowledge of his parents by a Catholic maid, and brought to Rome to the House of the Catechumens. A case which in a short period echoed at national and international level. Between 1859 and 1860, with the annexation of the territories of the pontifical legations to the Kingdom of Italy, except Rome, the Jewish communities regained freedom. A first census of a united Italy gave information about the Jewish communities, and also about the Jews of Bologna, about their numerical consistency, literacy rates, social composition: the Jewish Bolognese are 229, of which 136 men and 93 women, mostly dedicated to banking activities, grain and canvas trade; the illiterate Jewish are 5,8% compared to the national average of 64,5%.

In 1860 the law Rattazzi, which regulated the life of the Jewish communities, was extended also to Bologna; in 1864 was founded the Jewish voluntary association in Bologna, association which later will take the name of Community. In Italy, emancipation formed the decisive boost for the start of a new and intense cultural, scientific and thought effort of the Italian Jewish communities. The Italian Jewish world was able in a short period of time to express cultural models, which in most cases managed steering functions of the cultural organization of European Hebraism. As they could access to studies and jobs without the restrictions of the past, many Jewish Bolognese could achieve considerable positions in the city life and contributed to the political, cultural and economic life of the city; many pursued brilliant careers at the University of Bologna. The first World War represented an important step for the history of the Italian Jewish communities: it’s clearly evident the idea of a continuation of the emancipation of the Risorgimento and the road to the progress of the liberal democracies. We can understand the strong membership of the Italian Jewish people in the first World War and so also of the ones from the Bolognese community. The measures taken in order to “protect the race”, decided by the fascist governement in 1938, had devastating effects in the Italian academic world and also in the one from Bologna and in scientific research, effects which didn’t end with the end of the second World War. The University of Bologna witnessed the expulsion of many Jewish teachers: all victims of the persecution, many didn’t come back after the war, for others the reintegration was even humiliating. The esteemed jurist Edoardo Volterra was the first rector of the University of Bologna after the Liberation.

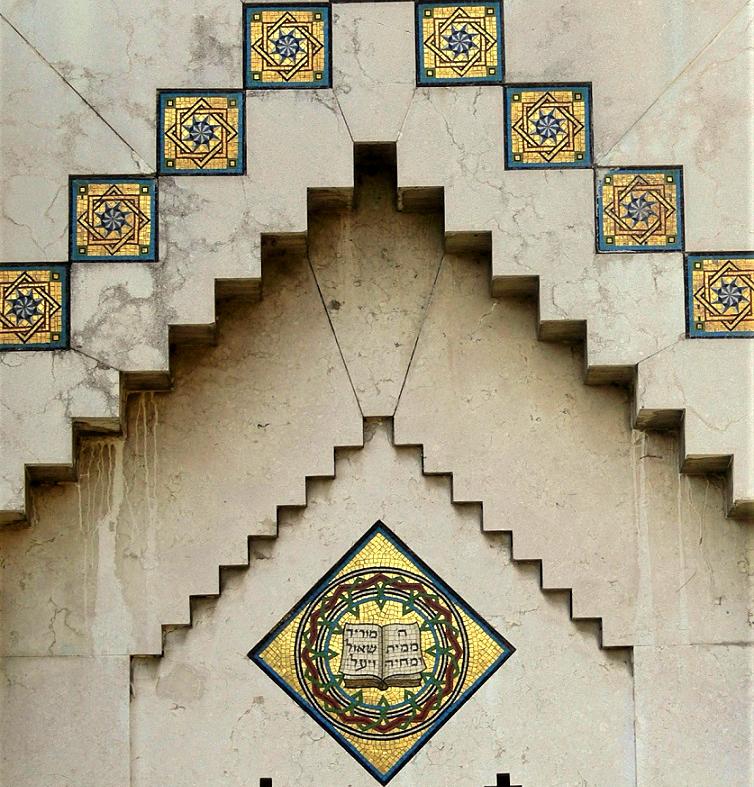

On the 7th November 1943 began in Bologna the deportations to the nazi death camp: there are 85 confirmed victims, among them the rabbi Alberto Orvieto. Among the Jewish Bolognese who took part in the war for liberation, many were decorated for bravery. The Jewish Bolognese community was reconstituted the days immediately after the liberation of Bologna in 1945. The Temple, destroyed during the war in 1943, was rebuilt and inaugurated in 1954. The community of Bologna, with headquarters in street de’ Gombruti 9, alive and present in the cultural urban life, is one of the 4 active communities in the regional area of Emilia-Romagna.

Traduzione di Matilde Zanotti, in collaborazione con il Liceo Linguistico Internazionale C. Boldrini di Bologna, marzo 2022.