Schede

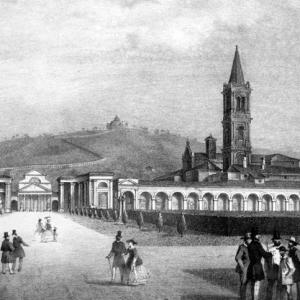

THE JEWISH CEMETERY

For Italian Judaism, not only the synagogue but also the cemetery is a place with a very strong identity. From the second half of the 19th century with the attainment of civil and religious rights, the cemetery became a new form of “visibility” in continuous dialogue between normative-religious issues related to tradition, and formal stylistic choices tending to adopt the architectural and decorative orientations of the period. In order to understand Jewish cemeteries it is also necessary to clarify some rules on funeral rituals and burial methods, which along with the succession of historical circumstances and the place where they were observed have had a strong influence on the image of these places.The land is usually on an east-facing slope to allow the tombs to face Jerusalem. Laws permitting, the corpse is lowered into the grave wrapped in a simple sheet to speed its return to earth, and for this reason cremation and exhumation are strictly forbidden. Essentially there are two types of tomb: the partially buried perpendicular tombstone known as a stele is very common and traditionally Ashkenazi, and the tomb consisting of horizontal stone slabs which is normally used by families of Sephardic origin. In addition to symbols of the Jewish religious culture (the seven-branched candelabra, star of David, scroll of the Law etc.), a picture of the deceased can be seen in some tombs, in line with a usage adopted after emancipation but not conforming to Jewish tradition. As for the history of Jewish burial places in Bologna, over the centuries scholars have referred to ancient cemeteries, the largest of which was allegedly the 16th century one in what is now via Orfeo at a nuns’ convent. The four monumental gravestones in Bologna’s Civic Medieval Museum are said to come from this cemetery. The first information on the establishment of a new burial place in Bologna Certosa for the reconstituted 19th century Jewish community comes directly from the memoirs of Marco Momigliano, Chief Rabbi of Bologna from 1866 to 1896: “I arrived in Bologna on 30 July 1866. My first thought was to discover the exact number of Jewish families living here. After a thorough investigation I was informed that the number of Jews amounted to about three hundred. (…) This new communion took the name Jewish Association (…) lacking everything needed and even a cemetery. My first thought was to turn to the City Hall to be entrusted with a plot of land to bury our deceased fellow believers. The small number of Jews living here did not permit the collection of the sum required to purchase it and provide for the necessary chambers for funeral ceremonies and the saying of prayers for the souls of the dead. The City Hall gave us much support, and public praise goes to it for this, as following my request it built at its own expense the boundary walls, the two chambers necessary (…). As soon as the works were complete I had the remains of the deceased buried in the Protestant cemetery moved to our cemetery. In 1869 our association had the cemetery it needed.” The present Jewish area covers a vast area of around 7000 sq. m. split into three parts. The oldest section of approximately 1000 sq. m. with around 384 tombs and the mortuary chapel, currently consisting of one single very simple room with no fine architectural features, has over time taken on a monumental appearance. It is therefore worthy of historical-artistic consideration and also represents a cross-section of the community’s history from its foundation in the early decades of the 20th century. As for the design of the tombs, the eclectic mix of styles, linked in particular to the orientalist iconographies which characterised synagogue architecture from the second half of the 19th century to the first two decades of the 20th century, foresaw a non-trivial transposition into individual funerary architecture. According to the architect Marco Treves, a central figure in the architectural definition of the new image of post unification Italian Judaism, “a truly “Judaic” style that as far as I know does not exist”. This is why the designs of the wealthiest Jewish families’ burial monuments often tend to follow a “Jewish declination” of the characteristic architectural eclecticism of the period. Reference is often made to Solomon’s Temple, adopting a character between the Assyrian-Babylonian and Egyptian one, or to the style of the second Temple, which in addition to the two previous styles included features of Greek art. In Bologna Jewish cemetery also, the traditional simple steles were very soon flanked by real “monuments” which in addition to creating an iconographic transformation gave rise to a new general view of the place. It is worth recalling in this connection the Liberty tomb built in 1911 by the sculptor Silverio Montaguti for the Zamorani family, the “oriental” chapels of the Padovani (1872), Zabban (1924) and Del Vecchio (1929) families, the large enclosure with a chapel built in the thirties for the engineer Attilio Muggia’s family, and the Finzi shrine, a fine example of modernist architecture designed in 1938 by the architect Enrico De Angeli. 2008 saw the completion of a first upgrading phase of Bologna Jewish cemetery, with the restoration of 89 of the most historically and artistically interesting tombstones. This work was intended to initiate an enhancement strategy for the cemetery, which in addition to preventing its progressive deterioration may also promote knowledge about this very special place, an interweaving of architecture, sculpture, nature, and individual and community memorials. (Andrea Morpurgo excerpt from R. Martorelli (edited by), La Certosa di Bologna - Un libro aperto sulla storia, exhibition catalogue, Bologna, Tipografia Moderna, 2009).

On 21 July 2011, the renovation of the Temple for funeral rites was inaugurated with funding granted to the Jewish community of Bologna by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. A number of inscriptions were affixed on that occasion. The first, outside: מכלכל חיים בחסד מחיה מתים ברחמים רבים סומך נופלים ורופא חולים מתיר אסורים ומקים אמונתו לישני עפר מי כמוך בעל גבורות ומי דומה לך מלך ממית ומחיה ומצמיח לנו ישועה ונאמן אתה להחיות מתיםInside: בשעת פטירתו של אדם אין מלוין לו לאדם לא כםף ולא זהב ולא אבנים טובות ומרגליות אלא תורה ומעשים טובים AT THE TIME OF MAN’S DEPARTURE NEITHER SILVER NOR GOLD OR PRECIOUS STONES ACCOMPANY HIM BUT ONLY THE TORAH AND GOOD DEEDS ה׳ ממית ומחיה מוריד שאול ויע THE LORD HAS US DIE AND HAS US LIVE AGAIN HE HAS US DESCEND INTO SHEOL AND HAS US RISE AGAIN על שלושה דברים העולם עומד על התורה ועל העבודה ועל גמילות חסדים THE WORLD RESTS ON THREE THINGS ON THE TORAH ON WORSHIP AND ON GOOD DEEDS Temple bench epigraph: כי עפר אתה ואל עפר השובהצור תמים פעלו כי כל דרכיו משפטאל אמונה ואין אבלעדיק וישר הוא

The name we Jews use for the cemetery is “Bet ha Chajjm” “house of life” or in the specific case of Bologna, as placed precisely in the new entrance: בית מועד לכל חי “Bet Mo'ed Lekhol Chai” “meeting house for the living”. We may note - but also the masters of Jewish tradition do so with their teaching – that the word DEATH is very often omitted, even to indicate that state. Therefore, again according to Jewish tradition, even death is part of a stage of life and the cemetery is the absolute proof of this. It is also, as has been repeated, the utmost proof of the presence of a Community that disappeared from this city for some reason. As a Community, we can therefore only be satisfied that yet another step forward has been taken to set the local Jewish cemetery in order. At the time of refounding of the Bolognese Jewish Community, after the opening of the ghettos and emancipation, this was strongly desired by Rabbi Momigliano first and foremost and also all the Community as a fundamental point of reference, together with the Synagogue and the school. (Note by Rav Alberto Sermoneta, Chief Rabbi of the Jewish Community of Bologna).

THE CINERARIUM GALLERY AND THE ARA CREMATORIA

For a number of years, the subject of cremation of bodies shook Italians’ souls, and the medical-legal and ethical-religious conflicts made it particularly lively and intriguing. There was a real revolution in customs, moral principles and consolidated convictions. Hygienist doctors firmly supported cremation as a choice, considering it indispensible to prevent the pollution caused by decomposition of bodies in the grounds and waters of cemeteries located too close to town centres. They always countered the legal objections of those fearing cremation could become a means of exempting from criminal justice the discovery and investigation of deaths by murder, by demonstrating that even in ashes it is possible to discover traces of lead, copper, zinc and arsenic residues. In 1888, the possibility for citizens to choose cremation was finalised for the first time in the legislative corpus enacted by Francesco Crispi on the insistent prompting of Agostino Bertani, a hygienist doctor and man of the progressive left. According to law, the authorisation for cremation had to be issued by provincial doctors, while the Cities were obliged to grant areas for the construction of crematoriums and columbariums for urns. The ethical-religious objections still had to be fought. The Church considered burning bodies a barbaric tradition, while Christianity had taught people the cult of bodies, a cult strengthened with burial which was thought to be more appropriate to the religious concept of death and respect for the human body. Cremation was in fact seen as a dangerous modernisation of customs and the reform of a usual Christian “custom”. Burial ritual was another debated question and well aware of this were the advocates of cremation, who in addition to researching “modern” methods of cremation respectful of bodies of the deceased, took pains to conduct the deposition of ashes in cemeteries without spectacularity but with reverent rituals for remembrance of the deceased that respected private grief. Cremation spread in the final decade of the 19th century and cremation societies appeared in various Italian cities, including Bologna. The arguments that drove the promoters of the pro-cremation campaign in the city were no different from those debated nationally: cremation was presented as a civilising element, it built on health and hygiene assumptions but also on affirmations of declared secularism. It was supported by doctors, scientists, lawyers, politicians with radical and socialist tendencies, and ordinary citizens received from 1884 in the cremation society, which immediately set in motion the procedures for planning permission to build the crematorium temple and cinerarium in Certosa. In 1888 it was decided that the Temple must be built outside the cemetery boundary wall, to the south of the Jewish burial ground and next to the Protestant cemetery. On 5 July 1889 the Bolognese Ara Crematoria was solemnly inaugurated. 662 cremations took place in Bologna from 1889 to 1914. However, the City was more defaulting concerning its commitment to build the cinerarium. Even in 1894, cremation urns were crammed into the Certosa Hall of Mercy while setup work dragged on at the Temple, chosen to be the final resting place for urns. The cinerarium was inaugurated on 10 November 1895 with a solemn event that was rendered poignant by the parade of relatives in procession, carrying the urns to their final destination.

Fiorenza Tarozzi

Bibliography: M. Gavelli, F. Tarozzi, Anche sotto l’ombra dei cipressi: La Società di Cremazione a Bologna (1884-1914), in “Bollettino del Museo del Risorgimento”, a. 1987-1988; F. Conti, A.M. Isastia, F. Tarozzi, La morte laica, Turin, Scriptorium, 1988; F. Tarozzi, Una scelta forte: la cremazione, in All’ombra de’ cipressi e dentro l’urne…, Bologna, Bononia University Press, 2007.