Schede

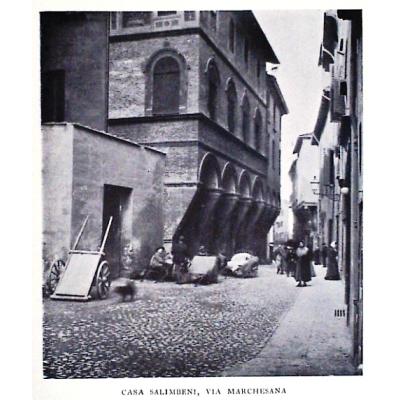

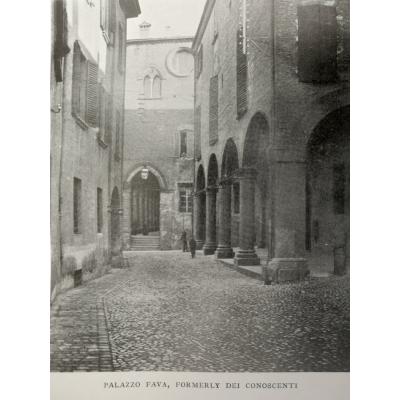

The January-April 1911 issue of "L'Archiginnasio", bulletin of the municipal library of Bologna, contains the review of a book by Edith Coulson James titled “Bologna. Its history, antiquities and art”. The review, written by Albano Sorbelli, director of the library and editor of the bulletin, opens with a few lines about the author: "The kind and learned Signora Coulson, who since long has the custom of spending many months of the year in Bologna, has been attracted by the glorious tradition and beauty of this city, to which she is therefore joined by a special and lively affection. We saw her often, indeed it can be said practically every day, bent over the large volumes of the Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio, for which she has a particular predilection, or admiring the houses and historical monuments of the city, or busy deciphering medieval writings in the State Archives. And the result of her precious, assiduous and diligent research is this splendid volume, published with great luxury and rich of illustrations”(1). Sorbelli, although pointing out that sometimes concepts or facts do not always find the absolute confirmation in the state of the art in research, expresses admiration and amazement in Coulson James’ ability to master “so well and in such a gentle form our events and the publications on the history of Bolognese art." “A volume that so neatly and clearly summarized the history and the monuments and the events and the artistic trends of our people,” Sorbelli states, “was still missing; and this serves splendidly to fill the gap."

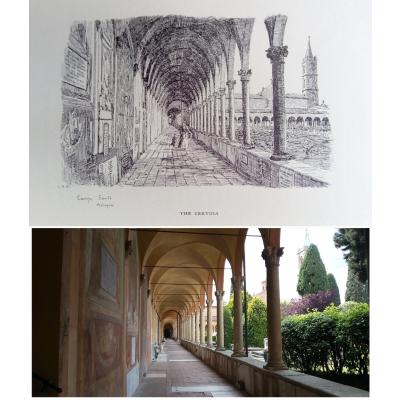

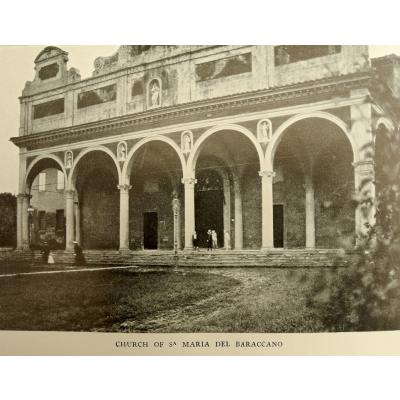

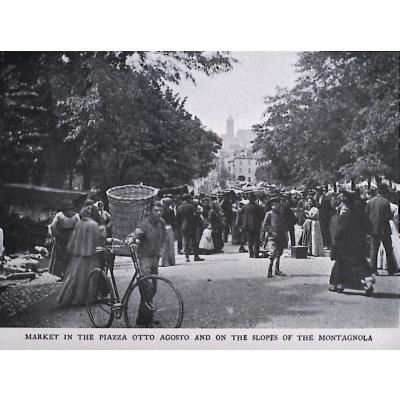

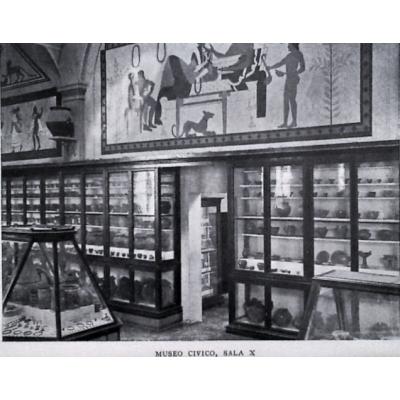

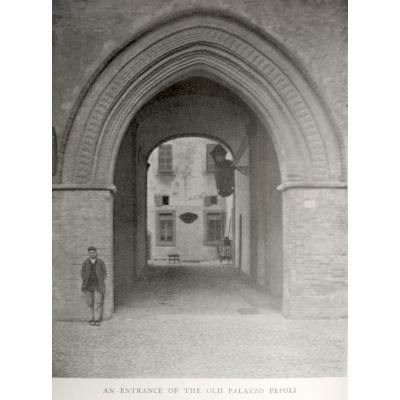

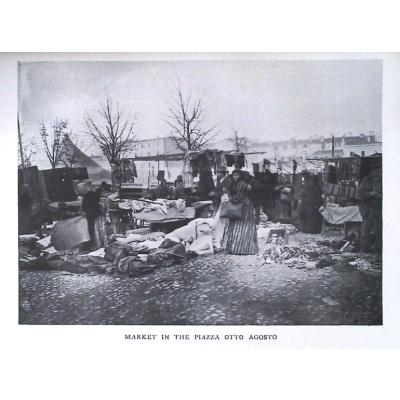

It is a publication in-octavo of over 400 pages containing 30 full-page drawings and 79 photographs, out of which 77 were taken by the author herself. Mary Hindle James Mackinnon, daughter of a brother of Edith Coulson James, wrote an autobiography in which, recalling the 1918 Christmas in the house of her aunt, at the time 58 years old, wrote: “Can you picture this little lady (she was about five foot or under) carrying all the equipment then necessary for photography - the tripod and plates and black cloth - and setting it up and fussing round and the interest of a crowd of spectators who soon gathered to watch”(2). It is very likely that Mary never saw the photographic equipment used by Edith and that it was much easier to transport than she imagines. As early as the last years of the 19th century, the photographic technique allowed the use of extremely handy machines and film negatives, much lighter than photographic plates, were increasingly widespread on the market; in general, the costs had become much more affordable and we are witnessing a proliferation of travel photographs taken by amateur photographers. Edith's younger brother himself, Lionel James, was part of the Argonaut Camera Club, a group of amateur photographers participating in the Argonaut yacht's study cruises in Greece and Minor Asia(3). In her book, acknowledging the work of the engraver and printer Emery Walker, Edith also makes express reference to "her negatives”(4) and in one of the occasional personal references that we find, she mentions a "travel equipment" in reference to her photograph of the altarpiece by Michele di Matteo Lambertini in the Abbey of Nonantola. Jokingly she writes: “It shall be left to the imagination of future pilgrims to the shrine to solve the problem of how the ancona was photographed with only the traveller's appliances for the camera. It is a very highly placed ancona. The Signora Sagrestana can tell.” Whatever the equipment used inside the abbey or on the streets of Bologna, it is easy for us to imagine, as her niece imagines, that Edith Coulson James aroused the curiosity of passers-by, and some photos from the book seem to testify it.

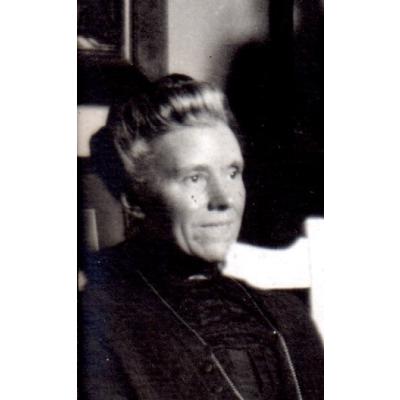

Edith Coulson James (London, August 30th, 1860 - Tunbridge Wells, June 2nd, 1936) grew up in London in a family of 4 siblings where she was the eldest and only girl. When her father, the lawyer George Coulson James, died suddenly in 1875, Edith was just 15 years old. Fortunately, Edith's mother, Susannah Elizabeth Rosher, came from a wealthy Kent family that made a fortune thanks to marriages, trade and construction development, and Susannah was able to provide for the family. The boys pursued military or academic careers but Edith always stayed with her mother, first in London and then, from 1897, in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, where she would keep her residence for the rest of her life.(5) In the obituary that appeared in the Kent and Sussex Courier of June 5, 1936, we read: “Miss Edith Coulson James, who died at East Court, Tunbridge Wells, on Tuesday, was in many ways a remarkable character. Her life of 75 years was shared between two intense loyalties: first to her mother, early left a widow, whose inseparable companion she became till well past middle life; and, after her mother's death, to Italian antiquities and art. […] When her mother died in 1902 there was a risk that the daughter might, like many devoted Victorian daughters, find herself stranded, with the bottom knocked out of her life. But Miss James had always been an eager student - she was for a time at Queen's College, Harley Street - and during travel in Italy with her mother had been greatly attracted to Bologna, a city, which so many travelers visit and so few know, and to the art of the great painter Francia.”(6)

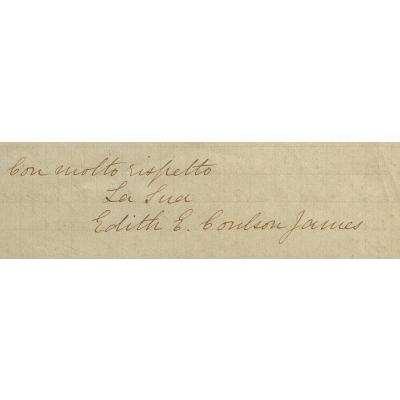

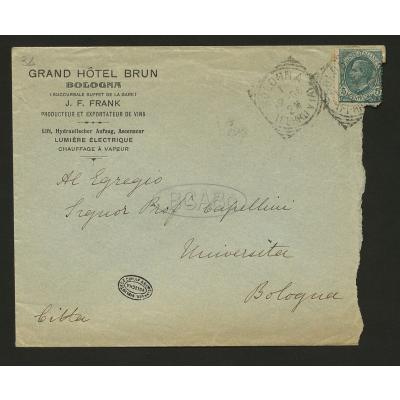

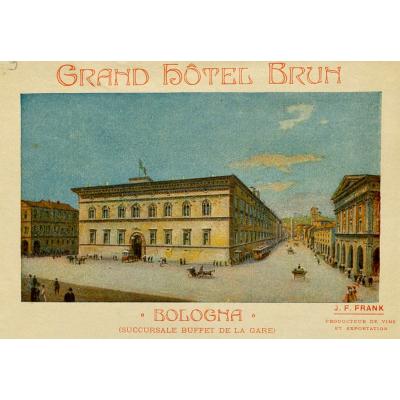

In a letter dated 1910 and addressed to Marquis Tanari, Edith writes: "On my first visit to Bologna I found the city very interesting and my interest and admiration have only always increased together with my knowledge"(7). We do not know when, traveling with her mother, Edith sees Bologna for the first time, but we do know that in March 1905 she is at the Hotel Brum for an extended stay, determined to undertake a research aimed at the publication of a book(8). The book was published in 1909 by Oxford University Press and in a review appeared in “The Athenaeum” of May 28, 1910, the book is defined as the most thorough and complete representation in English language of Bologna, “that city of colonnades and learned women”. The reference to learned women is not accidental. In the chapter “Distinguished professors and students of the University”, 7 pages out of 17 are dedicated to women and the sentence “The University of Bologna has always been honourably distinguished in that it has accorded perfectly equals terms to women students with the men” is certainly meaningful. No need to say that Coulson James gives too much credit to the University of Bologna. Furthermore, the biographies of the women we can read in the book are almost word by word taken from an 1845 book by Carolina Bonafede on famous Bolognese women(9), which in turn is based on unknown or not entirely reliable sources. Whether or not the information on Bitisia Gozzadini, Novella e Bettina Calderini, Laura Bassi, Anna Morandi Manzolini e Clotilde Tambroni is accurate, the choice to write about their lives and point out the true or alleged opening to women of the Alma Mater Studiorum reads as a statement in favor of women's education, consistent with Edith's commitment as a women's rights advocate and suffragist mentioned in the obituary on the “Kent and Sussex Courier”(10).

Edith Coulson James’ stays in Bologna and her researches and writing will not stop with the 1909 publication but will focus on Francesco Raibolini, better known as Francesco Francia, and will lead to the publication of several articles, mainly on The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. The list of her articles and booklet gives an idea of Edith’s constant commitment over the years. The opening words of a pamphlet published by Cappelli publishing house in Bologna in 1922 and titled "Gli autoritratti di Francesco Raibolini detto il Francia”, in a rough translation reads as follows: "The events of Francia’s self-portraits form a very interesting story. Very strange is the incredulity of some authoritative art critics, outside of Bologna, (...) regarding these self-portraits. We who know how reliable the Bolognese tradition is, find it very difficult to understand these doubts. But the disbelief is there, and to counteract it we must arrange all the evidence in order with the greatest accuracy." The events Edith Coulson James mentions are well described and contextualized by Maria Alambritis in “Edith Coulson James, Francesco Francia and ‘The Burlington Magazine’, 1911–17” (Burlington Magazine, January 2022), to which we refer for further information. What we find relevant here is how Emilio Negro and Nicosetta Roio, in their 1998 monograph on Francia more than once refer to the important discoveries of Edith Coulson James, “inexplicably ignored by a historiography that was misogynistic as much as obtuse”. Roio also wonders “what were the real reasons that caused art studies to reject and later on totally remove the hypotheses of Edith Coulson James”(11). But regardless the reliability of Edith’s authorship attributions, it’s impossible not to admire her systematic approach and above all her tenacious defence of her theses against well established art critics. Edith is a mature and financially independent woman who can boast the publication of a book for the illustrious Oxford University Press. Furthermore she was not devoid of initiative nor useful contacts if in 1911 she made it possible for Giorgio Trebbi to publish in England an article about Giovanni Capellini, with whom she had always been in contact and whose 50th year of teaching at the University of Bologna was commemorated that year. Nonetheless, to bear the impact of censure of very influential personalities in a typically all-male world must have required considerable courage and determination. On the other end, apparently Coulson James felt supported by scholars and critics active in Bologna and at the end of "Gli autoritratti di Francesco Raibolini detto il Francia” she is unable to resist a last little dig at the paternalism and ostracism of critics at home: “And I would like to let foreign critics know there are in Bologna in these days men of culture and acuteness who know well what is true proof. As there has been in Bologna, over the centuries, a cultured public constantly studying antiquities and homeland art.”

Works of Edith Coulson James

"Bologna: its history, antiquities and art", Oxford University Press, London (1909); "S. John the Baptist by Francesco Francia", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 20 (1911); "A portrait from the Boschi collection, Bologna", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 30 (1917); "The Auto-Retratti of Francia", Art in America, 8 (June 1920); Book Review of "Dante, suoi primi cultori, sua gente in Bologna" by Giovanni Livi, in The Burlington Magazine, vol 36 (April 1920); "The Auto-Ritratti of Francesco Francia?", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 39 (1921); "L'identificazione di un nuovo auto-ritratto di Francesco Francia", L'Archiginnasio: bullettino della biblioteca comunale di Bologna , 16 (1921); "Gli autoritratti di Francesco Raibolini detto il Francia", ed. Cappelli, Bologna (1922); "Un'altra pittura creduta perduta, del Francia, ritrovata", L'Archiginnasio: bullettino della biblioteca comunale di Bologna , 18 (1923); "Una pittura del Francia che passa sotto il nome di Garofalo nella Galleria di stato di Dresda", L'Archiginnasio: bullettino della biblioteca comunale di Bologna , 22 (1927).

Marina Zaffagnini, july 2022.

Aknowledgment | We would like to thank Mr. John Barnard for his precious support, his generosity in allowing the use of the documents from his family history website and providing me with further material. Mr. Barnard is a grandson of Lionel James, brother of Edith Coulson James.

Notes |(1) Texts originally in Italian are translated by the editor. (2) Mary Hindle Mackinnon, “For All That Time has Held”, NSW, Australia, 1993. (3) Images donated by the Argonaut Camera Club, including some film negatives by Lionel James, are accessible in the digital archive of the British School at Athens. From letters kept at the Archiginnasio in Bologna we know that on May 1, 1905, returning from one of these cruises, Lionel is in Bologna visiting his sister and it is not unlikely that the two siblings used the same camera. We also know that Edith took several photographs during her 1905 study stay as in August, from England, she sent a package with 20 copies of photos taken by her inside Museo Civico of Bologna to Edoardo Brizio, director of the archeological section of the museum. (4) “I am indebted to Mr. Emery Walker for care and artistic skill in reproducing from my negatives and drawings.” (p. XV). (5) Tunbridge Wells is located about sixty kilometers from London. Edith Coulson James, however, could count on Lyceum Club as a base in London. That is a women's club founded in 1904 whose aim was not merely to encourage meetings and discussions between members, but to provide women professionals, typically artists and writers, with a place for meetings with editors or various clients, a reference address in a prestigious area of London as well as the possibility of temporary accommodation. (6) “Death of Miss Edith Coulson James - A lady of intense loyalties”, Kent and Sussex Courier (5th June 1936), p.13. (7) Original text: “Alla mia prima visita a Bologna ho trovato la città interessantissima e il mio interesse ed ammirazione non sono che sempre cresciuti colla maggiore conoscenza”. From a letter from ECJ to G. Tanari, dated February 13th, 1910, Fondo speciale Giuseppe Tanari, cartone 50, 112, Biblioteca comunale dell'Archiginnasio, Bologna. Translation by the editor. (8) Letter from ECJ to E. Brizio, dated March 25th, 1905, Fondo speciale Edoardo Brizio, cartone V, 98-101, Biblioteca comunale dell'Archiginnasio, Bologna. (9) Carolina Bonafede, “Cenni biografici e ritratti d'insigni donne bolognesi”, Bologna, 1845, Tipografia Sassi nelle Spaderie. (10) “She was a keen supporter of the Woman's Movement and held meetings to forward the claim to vote.” Kent and Sussex Courier, June 5th 1936, p.13. (11) Emilio Negro e Nicosetta Roio, "Francesco Francia e la sua scuola", Modena, 1998, Artioli ed.