Schede

The clothing of a population has always been linked to its historical, political and economic events. An event such as the French Revolution had an effect not only on those who experienced it first hand and were its protagonists, but also on all those who lived in Europe at that time: the records of the 19th century testify how during the century it was increasingly difficult to recognise in the clothing of the population those differences that made it possible to distinguish a rich person from a citizen or an artisan. The ideal of equality promoted during the French Revolution, therefore, was also being reflected in the world of fashion.

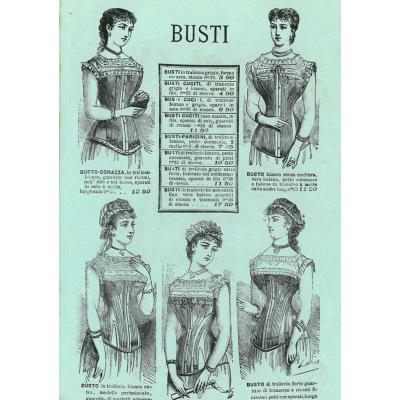

The changes in both men's and women's clothing, compared to the 18th century, were remarkable and linked to the new roles that men and women occupied within society: the man in the 19th century devoted himself to work in offices and shops, he no longer led his life in the living room and therefore needed to wear simple, practical and comfortable clothes; the woman, on the other hand, remained within the walls of the home, in charge of running the household. She began to give more importance to her physical appearance and her beauty, to some extent her clothing changed compared to the previous century, but the simplification would only take place from the end of the 19th century. Men in the 19th century immediately abandoned embroidered fabrics and wigs, the variety and liveliness of colours of fabrics in favour of a sobriety of costumes; for women, on the other hand, this change would take place very slowly and with a century of delay, when they too would be employed at work to replace their husbands, busy at the front during the First World War. Children during the 19th century, as in previous periods, will look just like adults, mirroring them and looking like miniature version of them, they will perfectly follow their styles and fashions. The changes that took place, especially in women's clothing, were due not only to obvious changes in taste but also to ideological (the emancipationist movements of women) and hygienic-sanitary (such as the abandonment of the narrow and unhealthy corset) reasons. Important changes also took place in the field of fabric production, with the use of means that reduced labour, new looms, the sewing machine and with the shift therefore of production from the seamstress working in her house to the craftsman working in his own workshop and then to the possibility of finding ready-made, made-to-measure clothes that could be bought in department stores and retail shops.

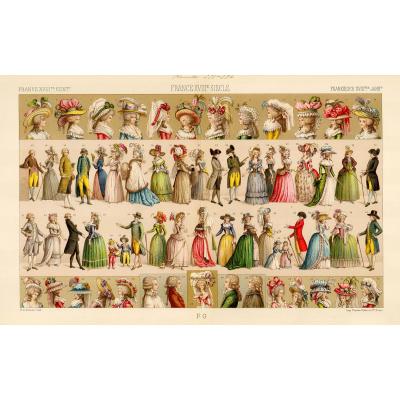

WOMEN'S CLOTHING - evolution | Women's clothing throughout Europe, throughout the whole 19th century, was linked to French fashion. The first period encountered in the 19th century in the field of fashion is the EMPIRE STYLE (1800 - 1820). It is the last phase in the evolution of the previous style, known as Louis XVI or Neoclassical, during which there was a great rediscovery of Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman art. In the early 19th century, excavations began in Pompeii, which contributed to a growing passion for classical art and the civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome, so much so that French women requested clothes in the style of those of these civilisations. From the statuary of ancient Greece and Rome, the non-use of colours and the style of dress were taken up, which for women resulted in a long dress called the Greek, Thessalian or Hellenic style. Made of thin fabric, it could often be dampened to be more adherent to the body; with short, wide sleeves or cut and fastened at the shoulder by a fibula (as in the case of the Greek chiton), the robe was fastened below the breasts by a ribbon or cord knotted at the back, with wide, deep cleavages that showed off the breasts more than they hid them. The skirt was long, reaching down to the feet, floated with every step of the woman, and at the back had a train that was gathered up by the forearm. Footwear and hairstyles were also taken from classical antiquity: open sandals held only by laces knotted at mid-calf, called "slave-style", and hair gathered up by a ribbon and held at the nape by a soft knot.

The abandonment of the classical language and thus of the Empire Style, in favour of a romantic language, occurred between 1820 and 1822. The clothes of the ROMANTIC PERIOD (1820 - 1845) began to become more complicated and the characteristics they presented were: the waist gradually dropping to the natural point; puffed or balloon sleeves, i.e. puffy and voluminous just below the point of attachment; bodice of the dress detached from the skirt (i.e. independent ending pointed at the front, tight and adherent to the woman's bust); use of bustiers to shape and thin the waist (which in this period is very narrow and highlighted by the combined use of puffy skirt and wide sleeves); skirt inflated by the use of crinoline (reaching down to the floor with bell-shaped development, wide at the bottom). Initially, several layers of fabric were used to inflate skirts, forming various petticoats: they were soon abandoned because they weighed down the figure and made the lady's movements difficult. Petticoats were therefore replaced by the first type of crinoline: a single petticoat to which horsehair and straw were pinned. This was followed by the crinoline made of light and independent metal hoops, so that women could lift it to overcome obstacles encountered on the way. Finally, a model of steel crinoline was patented by the Frenchman Delirac, which with a snap made the volume of the skirt retract, making it easy for ladies to pass through doors. The crinoline, however, also had disadvantages because: 1. its lightness could cause it to topple over in gusts of wind; 2. it did not allow two women to cross a doorstep or take a seat on the same couch at the same time; 3. it made the woman physically unreachable to the man who could thus not embrace her.

The crinoline was strongly criticised by men who also tried to discourage its use through the press. Numerous newspapers published reports that several women had been arrested and tried because a large amount of stolen goods had been discovered under their skirts. Husbands and fathers were therefore urged to prevent their wives and daughters from wearing this accessory, so that they would not be singled out as shoplifters while out for a stroll or fall into temptation while shopping. The female figure was referred to as "hourglass" because the combination of balloon sleeves and puffy skirt, narrow bust and slim waist made the figure appear to be divided into two separate parts. The period following Romanticism was the NEW ROCOCO (1845 - 1865), it saw a rapid involutional process of the crinoline which, after the success achieved in the Romantic period, led to its transformation after 1860. The original shape of the crinoline was transformed: the width of the hips shifted to the back of the figure. The volume and drape of the back of the skirt were then supported by the tornure, which consisted first of a horsehair pad, then of a starched cloth flounce, then of a series of horseshoe-shaped rings. Skirts in this period became flat at the front, with a string of fabric descending from the waist used to raise the front to prevent the woman from tripping while walking; they were still kept strictly long to the feet, the width of the bottom was maintained, and the hem was emphasised by the application of fabric flounces. In the back appeared the train, that is, a long tail that adhered to the ground and collected the dirt so much so as to deserve the ironic definition of "rubbish collector". Given the difficulty of cleaning this part of the dress, the end of the skirt, in contact with the ground, usually had a strip of black fabric that served to make the dirt collected less visible. With the disappearance of the crinoline from the second half of the 19th century the jacket began to be very popular, in the short bolero type or long to the hips. Always close-fitting to the bust and cinched at the waist, it was kept strictly closed by a long series of buttons and with a high, straight collar as women could not show the nakedness of their neck, chest or shoulders. A garment that, together with the jacket, was very successful was the blouse, characterised by the application of jabots, ruffles and flounces in the front, in correspondence with the chest as it was meant to conceal the thinness of the female bust and make this part of the body voluminous.

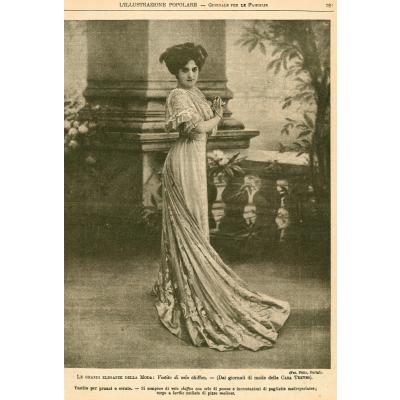

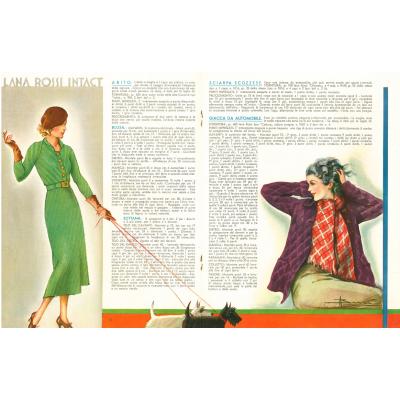

In the last two decades of the 19th century, a new type of dress appeared, called the "mannish dress". It consisted of a long-fitted skirt, gathered at the back by a pleat, cinched at the waist by a high belt and a short bolero open at the front. It was always paired with a fluffy blouse with high collars and rich lace. In Italy around 1888 the "mannish dress" was called a “tailleur” and this appellation was chosen due to the fact that such a garment had to be made exclusively by a tailor for men, who in French was called a "tailleur", to distinguish it from the dressmaker for women called a "couturière". The suit jacket was a clear reference to men's fashion, it proposed a rigorous and sober cut, and this was the reason for the use of the men's tailor, an expert in sewing men's clothes. In spite of its French name, the suit originated in England and the model had been spread throughout France. The tailleur was joined within a decade by its variant called the suit with jacket, i.e., a one-piece dress accompanied by a bolero. During the 20th century, women's everyday clothing became less extravagant, more rational and simpler. The woman in this period had a sinuous "S" line that was characterised by the front side out, the stomach in and the very slim waist. The common dress continued to be the suit, which sometimes, to be more faithful to men's fashion, combined the use of a waistcoat and an elegant, knotted tie that closed the collar of the blouse. Evening dresses continued to be rich in decorations and applications of pearls, sequins, precious stones; made of rich and elaborate fabrics; with wide cleavages and bare shoulders. A consequence of the First World War was the employment of women in the world of work, who went to occupy in factories and offices the places left vacant by their husbands engaged at the front. Hence the need for suitable clothing for the new role: skirts were gradually shortened to show ankles and calves, they were widened, and women often liked to wear knitted or crocheted cardigans, which were practical and soft. But the First World War meant that clothes were also simpler and stricter, almost devoid of ornaments.

MEN'S CLOTHING - evolution | In the 19th century the way men, the protagonists of everyday life, dressed became more and more practical, reflecting their condition; clothes became more and more "serious" in their fabrics and colours, giving rise to more simplified and severe clothes than those that had characterised the 18th century. Elements that characterised men's clothing in the 19th century were: the shirt, the tie, the waistcoat, the jacket and trousers. The shirt at the beginning of the 19th century was adorned, as in the 18th century, by the jabot, i.e., a lace ruffle embellished with tiny "music-paper" pleats that adorned the entire chest from the collar. With the gradual disappearance of the jabot, shirts were closed at the collar by the tie, which initially consisted of a long white linen band that was knotted at the front after being wrapped around the neck. Tie knots underwent an evolution during the 19th century that gradually led it towards forms more similar to those of today. In the Romantic period, the tie knot was held in great esteem: knowing how to knot this accessory correctly was considered a genuine art, so much so that in 1828 a text was published, entitled "The art of tying a tie". Thirty-two different ways of tying a tie were taught in this volume, accompanied by illustrations. The knot was of such importance that as soon as a man entered a club, all eyes were fixed solely and exclusively on the tie, whose knot was carefully examined and possibly criticised: whether he was admitted or excluded from the club depended on it.

After a brief reappearance of the breeches (culottes), which survived for a while, first came the long trousers tight at the ankles, kept tight by brackets that passed under the soles of the shoes, then replaced by the tubular trousers. The waistcoat was another characteristic element of men's clothing throughout the 19th century, recovered after the period of the French Revolution, which had abandoned it. Originally made of refined and precious fabrics such as damask or brocade, then white and finally, at the end of the century, made of the same fabric as the jacket and trousers, to match them. Great importance was given to accessories: the pocket watch, the hat and the walking stick. These objects, like the clothes, underwent an evolution during the 19th century that gradually led them towards forms closer to those of today. The pocket watch was an object that a 19th century man could not do without, a symbol of elegance worn in the breast pocket of the waistcoat and secured by a chain inserted in the first buttonhole. For the rich the pocket watch was made of gold while for the less wealthy it was made of silver. The hat at the beginning of the 19th century resembled the bicorn or "Napoleonic-style" hat in use in the 18th century. It was later replaced by the top hat's predecessor, with a body tapered towards the dome, and then by the top hat proper. In the 1930s, the Frenchman Gibus invented a top hat with springs inside it that allowed it to be squashed and carried easily under the arm; in the 1960s in Italy, a hatter, inspired by a news event, created the homburg. This hat had a crease at the dome and took the shape of the hat worn by Member of Parliament Cristiano Lobbia who, after an aggression he had suffered, found his hat crushed at the top. At the end of the century, the straw hat appeared and with the new century, headgear fell into disuse. The walking stick appeared after the first decade of the 19th century as the 18th century custom of carrying a sword, used not only as an accessory but also as an instrument of defence, was revived. Later, the rapier was concealed inside the cane of "swordsticks", the first walking sticks that became man's new and inseparable accessory. Later, the cane barrels were made of fine wood, the handles were chiselled and made of gold, silver or precious stones. In the 20th century, men's clothing remained virtually unchanged; fashion was still linked to England and the basic garments remained jacket, trousers, waistcoat and tie. As in the past, great importance was given to accessories: the tie could be knotted like a butterfly, as it is today, and fastened with a brooch. In 1900, trousers were characterised by turn-ups at the hem, a feature taken from English fashion. This custom arose following a trivial episode: the then King of England Edward VII, present in a muddy hunting ground, tucked in the hem of his trousers so as not to soil them. English men soon used this trick so much that tailors made trousers in this way.

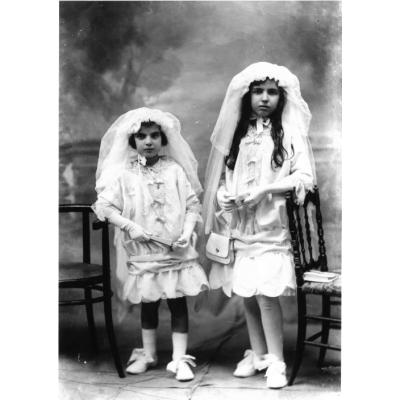

CHILDREN'S CLOTHING - evolution | Until the age of four, there was no distinction between the sexes as boys and girls dressed identically: they wore a woman's dress that emphasised the link with the universe in which they were growing up. This dress was also adopted for reasons of practicality, hygiene and probably also for economic reasons. This custom remained unchanged throughout the 19th century until the first thirty years of the 20th century. The clothing of boys and girls began to differentiate from the age of five. Children in the 19th century, as in earlier periods, were dressed like grown-ups in miniature and followed the trends and fashion developments of adults. Children's clothing mirrored that of adults: thus, in the early 19th century, girls wore long tunics pulled tight under the breasts (like their mothers' Empire-style dresses) while boys wore tailcoats and long trousers. In the mid-19th century, girls' dresses were characterised by wide skirts and balloon sleeves, elements of the Romantic period; boys, on the other hand, like grown men, wore suits consisting of jacket, tie, waistcoat and tubular trousers. With these types of clothes, children were not free in their movements and could not indulge in the spontaneity characteristic of play; they felt awkward and always had to be careful not to crease or soil their clothing.

Finally, from the end of the first decade of the 1900s, the idea that children's everyday clothing should follow criteria of simplicity and practicality became widespread. Gradually over the course of the century, thanks to the current coming from England, fashion became more adapted to the needs of children and, unlike in previous centuries, tailoring tried to respond more and more to the needs of childhood. Slowly, clothes were created specifically for children, i.e., practical, light and hygienic; only on big occasions (such as communions or special events) were children still forced to wear elegant clothes. But the changes did not only concern clothing as evolutions also involved accessories such as footwear: if during the 19th century children were forced to wear high-heeled boots, in the early 20th century they were given practical and comfortable low-heeled shoes with laces. During the 19th century, during the reign of king Umberto I, a new type of dress appeared for older children, called "marinare". This garment was taken from the sailors' uniform and consisted of a navy-blue blouse, repainted at the waist and distinguished by a large white piqué collar knotted at the front and square at the back (sometimes at the corners it was adorned with small anchors). The jacket was combined with a pair of shorts reaching the knee, at which they had a band; short white or blue socks; black or brown flat shoes and a hat in the shape of a sailor's hat. This outfit was almost the same for boys and girls, except for the trousers, which for girls were replaced by a short, pleated skirt. Generally, the colours of this uniform were white and blue (sometimes also grey and black) and the variations were exclusively related to the fabrics used to make them, which therefore varied in quality and heaviness according to the season.

If until the end of the 19th century children's fashion was influenced by that of adults, with the new century the situation was reversed: skirts became shorter first for girls and later for women.

Silvia Sebenico

Translated by Lorenzo Rocco, 2022.