Schede

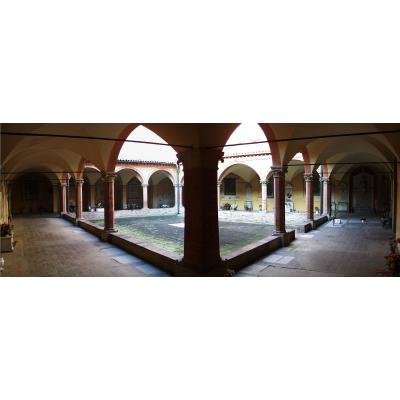

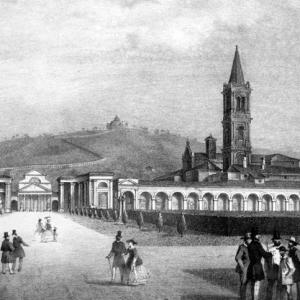

These places were part of the ex-monastery and they were among the first to be reused at the beginning of the 19th century. It’s in these cloisters that are located - like in the original “Chiostro Grande”, now “Chiostro III” - the first monuments either painted or made of plaster and stucco. The actual “Chiostro I° di Ingresso“ was the one that overlooked the kitchens, meanwhile the “Sala della Pietà” (Pity’s Room) was the “Refettorio” (dining hall). The “Chiostro delle Madonne” (Madonnas’ clositer) was a fifteen-century little space which served as a meeting point between the “Sala del Capitolo” (now “Cappella della Madonna delle Assi”), the Church and the “Chiostro Grande”.

The most important architectural structure in this area of the cemetery was made by Angelo Venturoli (1741-1821) in charge of building in the ex “Sala del Refettorio”, now “Sala della Pietà”, the stairs that connect the ground floor with the basement. In 1816, the architect made a little neoclassic masterpiece, all based on the purity of the oval’s volume where two stairs meet at the center, while not giving space to ornamentation. The Baldi Comi family’s memorial was also overall designed by Venturoli, with the assistance of Giovanni Putti for the sculptures and Flaminio Minozzi and Giacomo Savini for the paintings. This wonderful memorial perfectly represents Bologna’s neoclassical style, clearly distant from the one that spread in Rome and Milan. The fifteen-century “Chiostro delle Madonne” takes its name from the presence of numerous images of Virgin Mary preserved in cases. Hailing from the city churches shut down throughout the 19th century, they represent an untouched evidence of the period when Certosa was a museum, during which monuments and memories of the city, coming from streets tabernacles and religious buildings gradually demolished and abandoned, were collected. The detached frescoes date back around the 14th and 16th centuries. A punctual description of some of the holy images was printed in the 35th number of the periodical “Il Piccolo Reno”, published in Bologna in 1846. This Cloister is also called “Chiostro dell’Ossaia” (Cloister of the charnel house), as one of the first charnel houses was made here by reusing the big water tank located in the center.

From the Cloister you have access to the “Corridoio dipinto” (painted hallway), the only intact proof of the decorations of the monastery out of the Saint Girolamo’s church. The frescoes were made by Padre Marco from Venice in 1638 and they portay the main episodes of San Bruno’s life, the founder of the Carthusian order. Next to the hallway we have the “Cappella della Madonna delle Assi”, already know as Sala del Capitolo del Monastero. The big baroque shrine nowadays keeps the Madonna coming from the homonymous chapel in the city, but originally it stored the seventeen-century “Risurrezione di Cristo” (Resurrection of Christ) by Giovanni Francesco Gessi and Francesco Albani. Up until now, the big paintings by Nunzio Rossi (Natività) and Lucio Massani (Salita al Calvario) were stored here, but after the restauration they have been moved to Palazzo d’Accursio for better preservation. Along the walls of the “Chiostro I di Ingresso” (Cloister first of entrance) are kept important plastered and painted monuments of the early 19th century. We can find here the works of Giovanni Putti (Fornasari, Maldini), Giacomo De Maria (Bersani), Alessandro Franceschi (Giro, Persiani). The original Prior’s cell came to be the “Sala del Pantheon” (Room of the Pantheon) or “of the most well-known people of Bologna, planned by Giuseppe Tuberini (Budrio 1759-Bologna 1831) and with the ceiling adorned by Filippo Pedrini’s(Bologna 1736,1856) frescoes. In the last few lines of the 1801’s bill that informed the citizens of the cemetery’s establishment, it is written that “the same public representations will make sure that those majestic cloisters will be adorned with monuments devoted to virtue and to appreciation”. This was reinforced in the belief of the Assunteria del Cimitero, when a lot of citizens turned to it to obtain free burial areas for honoring their deceased, considered part of the city’s history. This possibility later took shape in the idea of destining an area of the cemetery to the worthy and well-know individuals. In 1812 in the protocol registers of the Assunteria del Cimitero, it is mentioned the entrance of a project for a secluded area of the same cemetery devoted to the memory of the eminent men of the city, document which unfortunately is no longer available. From the report written on the 19th April 1822, that the Assunteria del Cimitero sent to the colleagues of the Judiciary, they tried to find a specific place in the Cemetery where to locate the remains of the people who, by the Judiciary’s definition, had been declared “eminent and deserving of the homeland”. The Basement of the room had to house 40 graves, which were to have a gravestone without decorations and a bust on a marble shelf, made by locals artists. The given indications were partially followed and, while the underground part came to be naked, the wide space above was decorated by Giuseppe Tubertini’s simple but impressive work crowned with the allegorical fresco by Filippo Pedrini located in the center.

Later, in 1911, the Town Council debated the location of the numerous marble busts stored in the Pantheon and a relocation was proposed. Everyone had a say on this: the Senator Sacchetti wanted them in the Palazzo Civico, Professor Faccioli thought they’d be better in the Sala della Pietà, Mr Collamarini wanted to build an outdoor exedra. The Council suspended every decision on the matter and the busts remained stored in the Pantheon up until the thirties, when they were moved to the Sala d’Ercole in the Palazzo Comunale. From there started a period of abandon and decay, with the loss of the majority of the marble portraits. The following passages, excerpts of two of the most important ninteen-century guides of Bologna, show how the Pantheon was gradually gaining more importance in the city’s memory. From Giovanni Zecchi’s “Descrizione del cimitero di Bologna” (Description of Bologna’s Cemetery), Bologna, 1829: “ It was recently built (with architecture) by Giuseppe Tubertini. The ceiling is painted with the sfondato technique: a very elaborated work by Filippo Pedrini, which will get the recognition it deserves as soon as it will be seen by a clever audience. In this painting it is depicted the triumph of Religion in the temple of Eternity where Felsina introduces the holy and profane sciences, and liberal Arts. The walls of this room will be adorned by some full-scale marble busts put on unvarying shelves, and with their inscriptions they will show the effigies and the praise of the nation’s worthy individuals, who have been deserving of being remembered by the posterity.” From Girolamo Bianconi, “Guida per la città di Bologna e i suoi sobborghi” (Guide of Bologna and its suburbs) Bologna, 1845: ”Not so far from this place you can see a roundabout, destined to keep the ashes of Bologna’s eminent personalities and decorated by the painter Prof. Filippo Pedrini who portrayed in the vault the triumphant Religion seated near the Temple of Immortality, granting to Felsina, lead to her in front of the Genie, the implored immortality as a reward of her sons’ glorious acts for the motherland, the value and virtue of whom are symbolized in various figures that surround her. Over them, Fame spreads out their immortal names in the furthest streets: in the background flows the river Reno, which is portrayed by the figure of a bearded old man.

Traduzione a cura di Monari Martina, Sveva Reali, Elisa Caridei and Alice Zanasi classe 3G, nell'ambito del progetto di Alternanza scuola-lavoro 2018/19 con il Liceo Ginnasio Luigi Galvani di Bologna.